BGP Route Hijack Incident Review

This is the fourth blog in a series looking at BGP security issues like BGP route leaks and BGP hijacks. The first blog examined trends in BGP security incidents. The second and third part in the series looked at route leaks, and this piece will do a deep-dive into real-world BGP route hijack examples.

What is a BGP Route Hijack?

A BGP route hijack happens when an autonomous system (AS) claims to be the origin for a network that has been assigned to another AS. For example, in Figure 1, AS 5 generates a BGP update message claiming to be the origin for prefix P, which is owned and used by AS 4.

Diagram of a Malicious BGP Hijack

This message is received by AS 5’s AS neighbors, which are AS 2 and AS 3. Depending on their policies, AS 2 and AS 3 may or may not accept the announcement. In this example, suppose that AS 2 discards the announcement while AS 3 accepts it, and its BGP decision process decides that the hijacked route is the best path to reach the destination P. Thus, AS 3 propagates the hijacked route to its BGP neighbors, which can again consider the hijacked route as the best path. Suppose that similar to AS 3, AS 1 is affected due to poor input policies. This would result in all traffic from AS 1 and AS 3 that’s directed to P be forwarded instead to AS 5 instead of AS 4.

At this point, the destiny of the traffic really depends upon the intentions of AS 5. If the hijack was created by mistake, the traffic will most probably just drop upon reaching AS 5, causing a denial of the services running on P. On the other hand, if the hijack was done on purpose, AS 5 could inspect the traffic searching for sensitive information, or even worse, could impersonate the services running on P with the aim to steal sensitive information such as login credentials.

AS_PATH Forgery Hijacks

This kind of hijack is often called mis-origination because the most-right AS in the AS_PATH of the hijacking route is not the legitimate origin (AS 5 vs AS 4 in the example), and it is rather easy to spot while looking at the AS_PATH. More complicated versions exist, like the AS_PATH forgery. In this hijack version, (Figure 2) the attacker AS deliberately alters the AS_PATH by appending the legitimate origin AS into the AS_PATH to make more difficult the hijack to be detected by monitoring systems.

Diagram of an AS_PATH Forgery

Real-world Origin Hijack: Cutthroat Island… But Just for a Few Minutes

In 2019, one BGP hijack incident involved an AS controlled by the Taiwan Network Information Center (TWNIC). This incident (figure 3) wasn’t largely covered by the media as it lasted only a few minutes and end users were not significantly affected. However, it is an interesting case to analyze because it is a perfect example of an origin hijack.

Diagram of a 2019 Origin Hijack

The TWNIC has been assigned the network 101.101.101.0/24, on which it runs a public DNS project called Quad101. On May 8, 2019, around 15:08 UTC, the Brazilian AS FibraPlus (AS 268869) started to originate by mistake the Quad101 network, sending this BGP route to its provider Claro Brasil (AS 4230). Claro Brasil accepted and propagated this announcement to its BGP neighbors, contributing significantly to spread the hijack.

Table 1 shows the routes hijacking the Quad101 network as perceived by three different collector peers. The most accurate AS in each AS_PATH is the AS number of FibraPlus (AS 268869) and not the TWNIC AS.

Table Showing Destination and AS_PATH

The Quad101 network has been originated at the same time by two different origin AS’s: FibraPlus in Brazil and TWNIC In Taiwan. Thus, by looking at the amount of FRT peers that announced the hijacked route to a route collector (Figure 4) there is no surprise in seeing a different behavior depending on the registry of the peer’s members: the peers in APNIC which are closer to the legitimate origin tended to use the legitimate route, while One possible explanation of this behavior is that many AS’s in LACNIC found the hijacked route more appealing in terms of AS path length the peers in LACNIC closer to the hijacker tended to use the hijacked route. Since the length of the AS path is one of the top criteria of the BGP decision process within an AS. Meanwhile, those in APNIC found the legitimate routes to be more appealing.

FRT Peers that Announced Hijacked Route

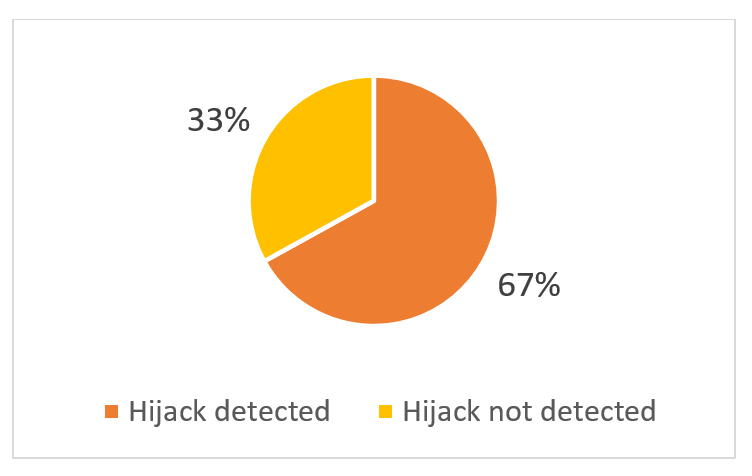

As can be seen from Figure 5, on a global scale the 33% of FRT peers did not announce to a route collector the hijacked route. Note that this does not mean that they didn’t receive the hijacked route, but simply that they didn’t announce it to the route collector.

FRT Peers Not Announcing Hijacked Route

Learn More About BGP Security

Our next blog looks at ways to overcome BGP routing’s insecurity.

Can’t wait for the next blog? Read our ebook Comprehensive Guide to BGP Monitoring for a deeper look into BGP routing