Subscribe to our

weekly update

Sign up to receive our latest news via a mobile-friendly weekly email

Our growing understanding of metastable failures is a great example of how continuous learning is critical to success in our profession.

The rise of new requirements, driven by generative and agentic AI, is another example. New applications, new customers, and new theoretical models will continue to expand our practice and allow us to build better systems for our customers. Great SRE teams are always learning, always curious, and always open to new tools and practices. The data in this year’s SRE report is a great place to start understanding the trends that will shape our profession for years to come.

Traditional approaches to measuring availability are concerned with error and success rates. Where they take performance into account, a threshold-based approach is most common, looking at successes within some timeout. Latency and throughput are measured and tracked, but seldom seen as availability indicators. As consumers of systems, we know intuitively that this approach is inadequate. Slowness is frustrating. As business owners we know slow performance costs us sales, conversions, and sends our customers elsewhere. Slow is as bad as down.

Over the last decade, as we have learned more about the causes of downtime, performance has become even more deeply linked to resilience. We have found that systems which slow down under load exhibit metastable states, behaviors in which systems stay down despite the original cause of failure being removed. These metastable failures, and related conditions like congestive collapse, are responsible for the longest, hardest to fix, outages. Performance, and how performance changes under load, are deeply linked to reliability and availability.

The mathematical theory and academic models of metastable failures are still an active area of research, but there are already practical steps practitioners can take. Testing the behavior of systems under excessive load and during simulated failures is highly effective at finding these behaviors. The combination of load and failure testing is especially powerful. Once we identify unwanted overload behaviors, we can identify the feedback loops that drive these behaviors (such as excessive retries, or lock contention), and fix them before they become an issue in production.

VP & Distinguished Engineer

Amazon Web Services

Reliability among uncertainty.

Systems fail in ways we do not expect. Yet we still predict. Practices evolve faster than documentation. Yet we still write. We think about what's next. Yet we respond to right now.

And while so much other research most certainly arrives with word-stuffed pages, as if more words mean more learning, we chose the uncertain opposite. That is, the strength of this report comes from its quiet simplicity, its restraint, and its lack of distraction. Each insight was written not to impress, but to simply present.

After eight years of tracing reliability’s arc, the view feels complete enough to pause and look back before seeing how far the boundaries have widened. Reliability is no longer only about sustaining uptime (was it ever?). It has moved from reliability to resilience, from uptime to experience, from toil to intelligence, from tools to strategy, and from systems to people.

There are still no certainties, but there is progress. And that remains enough reason to keep building.

GM, Catchpoint at LogicMonitor

When reliability is experienced as fast by users, reliability becomes reputation.

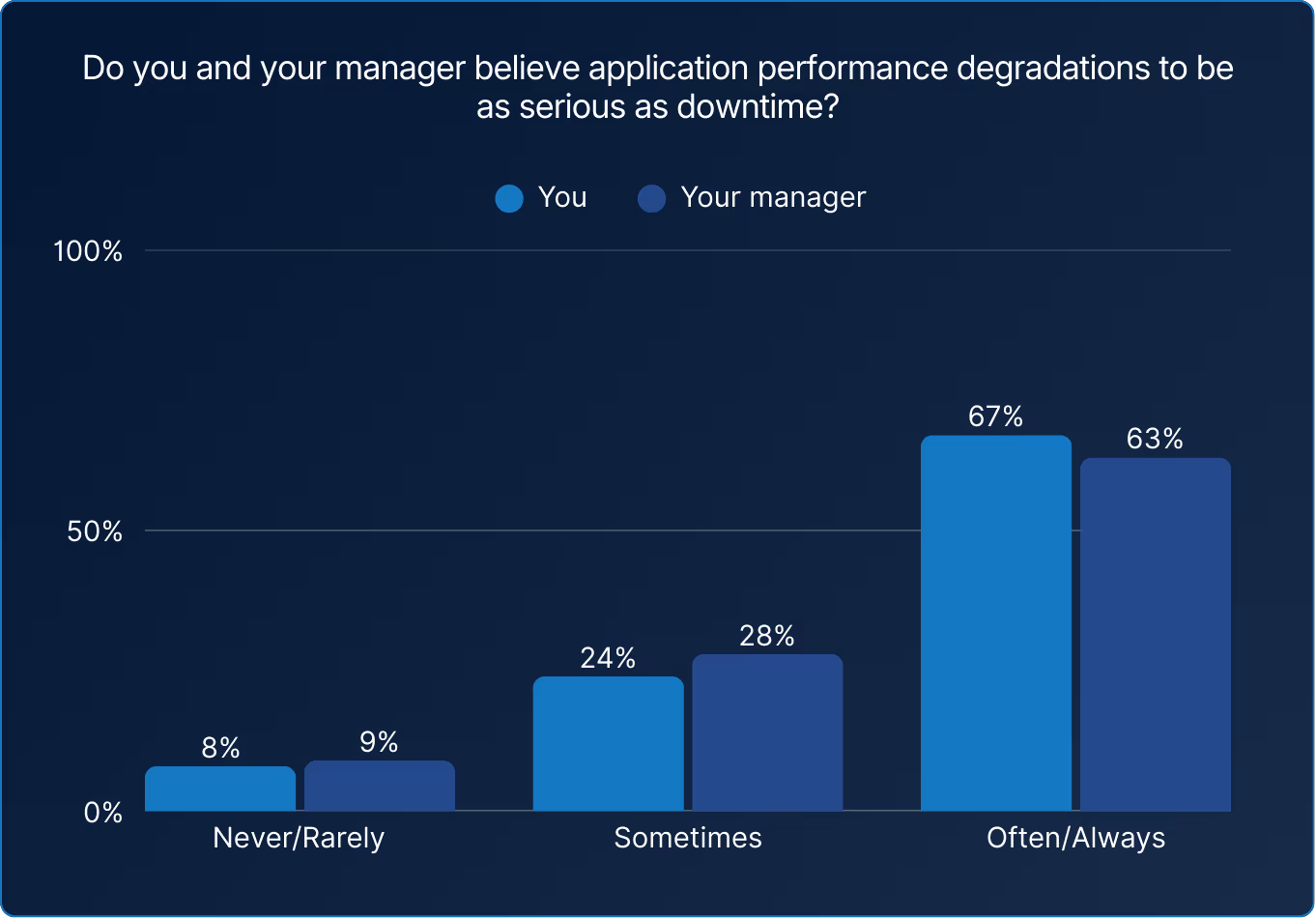

When a digital experience slows, users don’t care if it’s an outage or a delay. The result feels the same. The data shows reliability increasingly framed in terms of performance, not just uptime. Yet approximately a third of respondents still separate performance from uptime, meaning they never, rarely, or sometimes treat slow as being down.

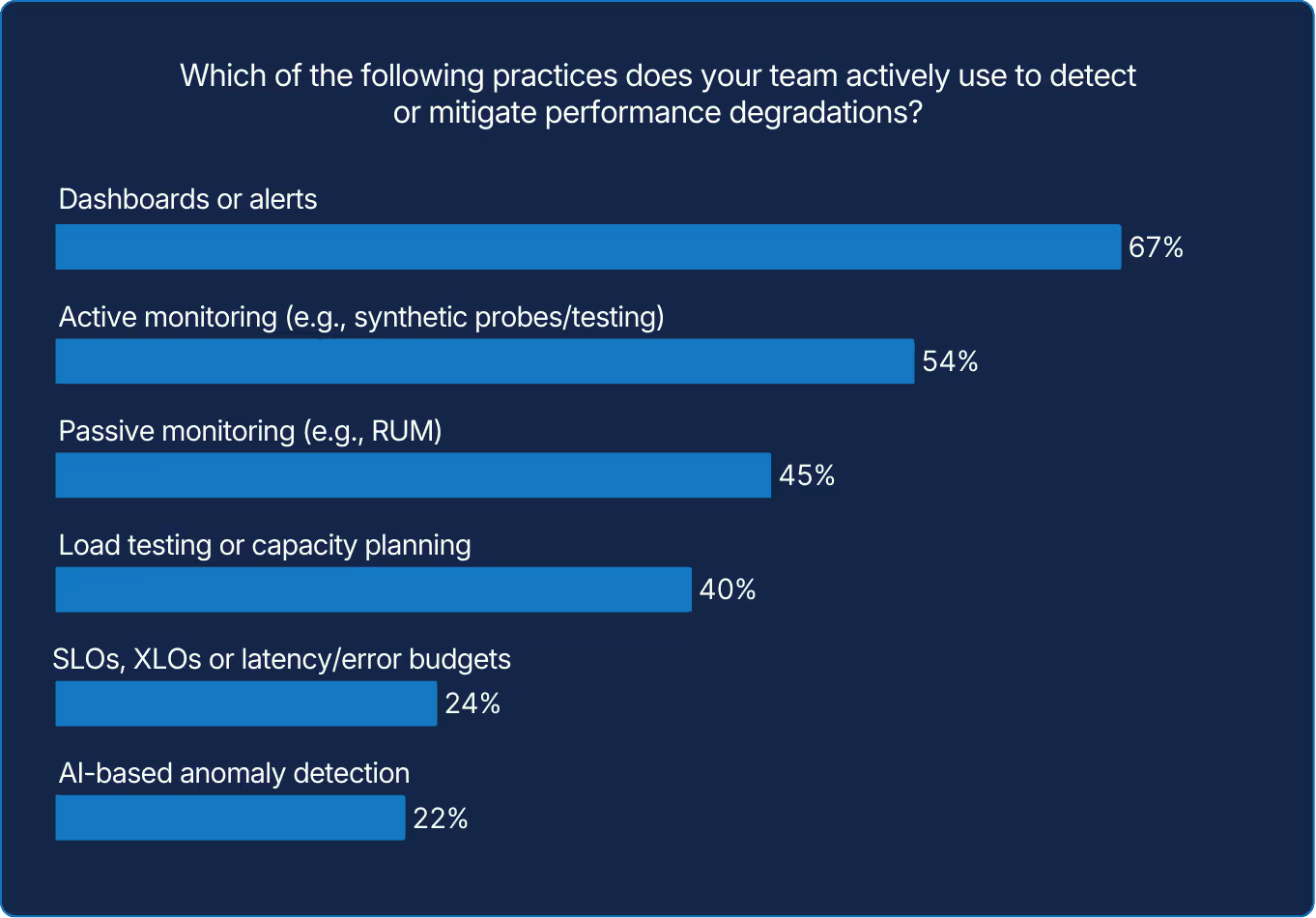

Teams trust their venerable tools, which may reflect familiarity, tooling maturity, or risk aversion. SLOs and AI, while still emerging, are present enough to suggest interest. The question may be less "if" and more "when" they become standard, which may mean different things to different organizations.

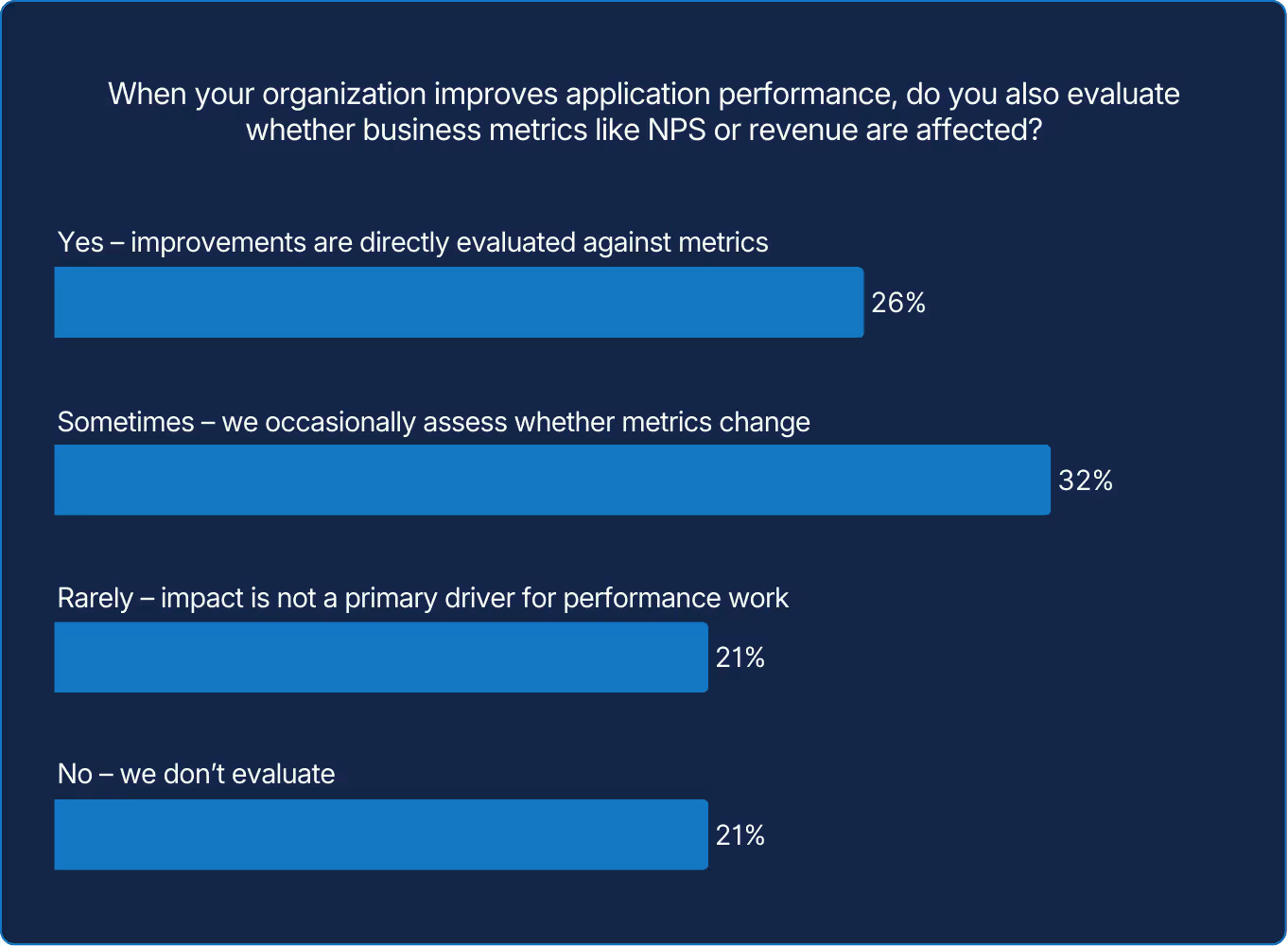

Most teams stop at technical metrics, leaving reliability's business impact unmeasured. In our opinion, this is a missed opportunity: organizations that do track the connection between performance and revenue will be better positioned to justify investment and demonstrate strategic value beyond engineering.

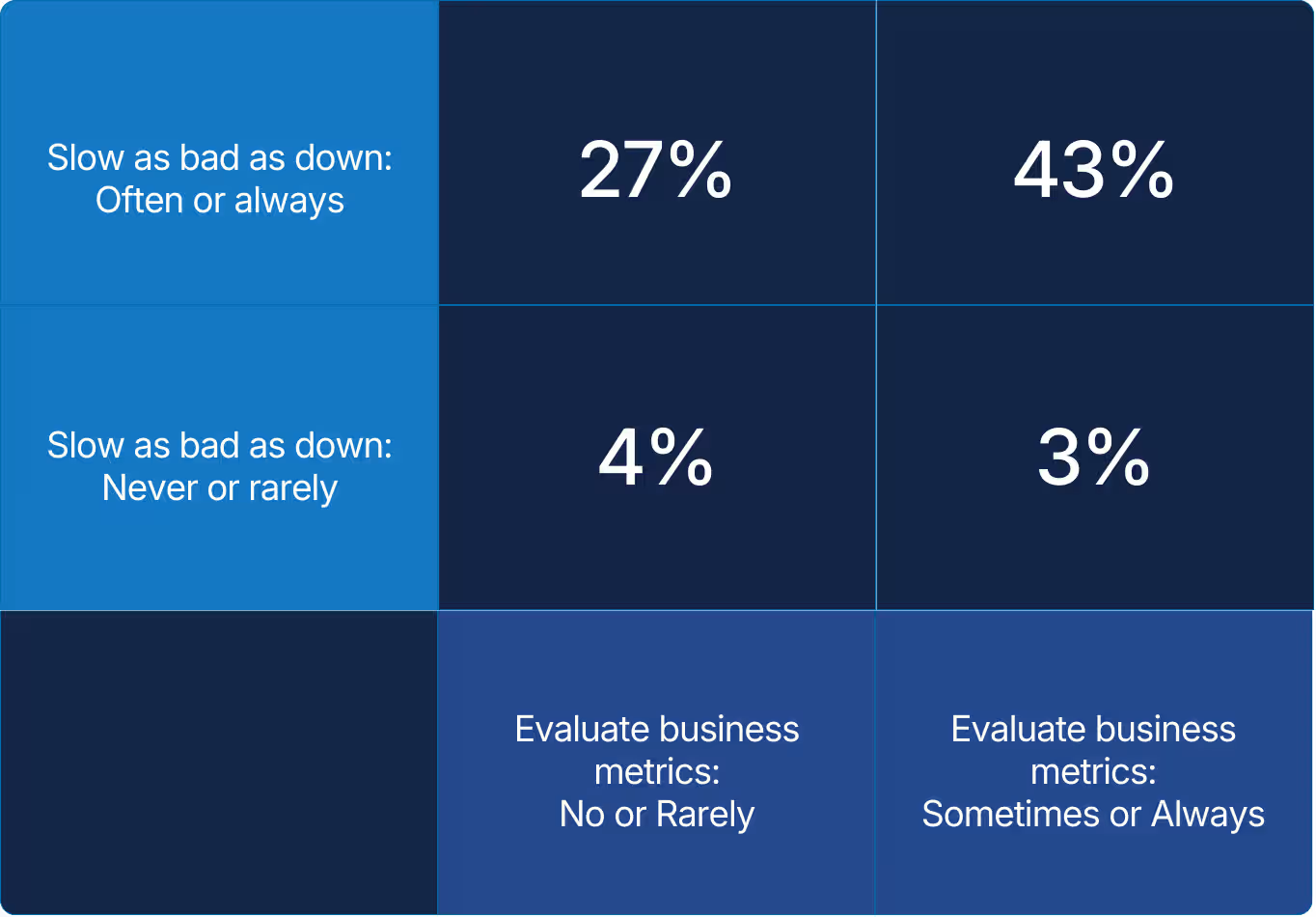

X axis: When your organization improves application performance, do you also evaluate whether business metrics like NPS or revenue are affected?

Y axis: Do you believe application performance degradations to be as serious as downtime*

*Sometimes 10% and 13% excluded from visual

When performance becomes a part of reliability, then it becomes an important business concern. Cultural mindset drives what gets measured and improved. Teams connecting belief and behavior show accountability and value in every fix.

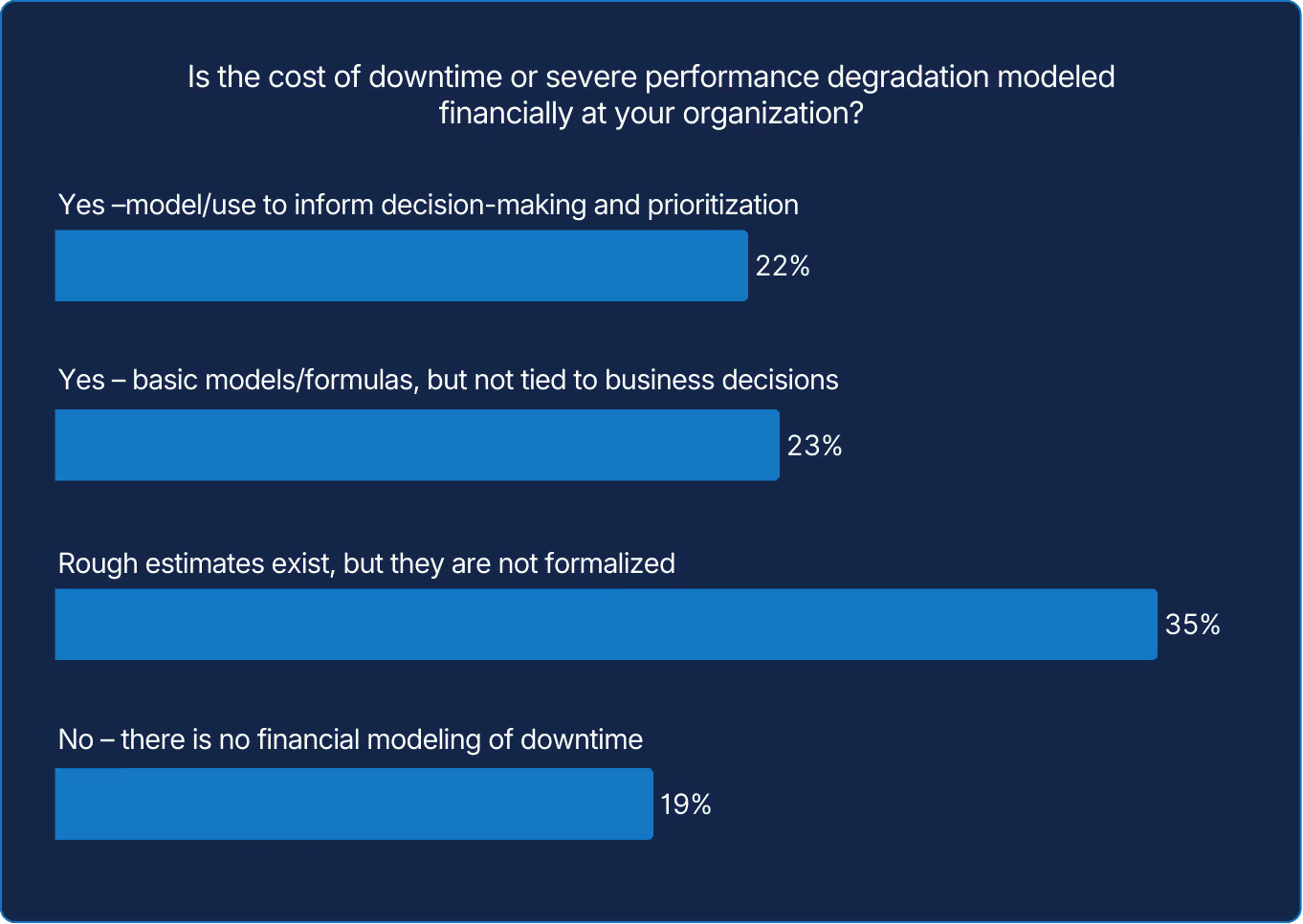

Without knowing the true cost of failure, reliability will remain a conversation in the server room but not in the boardroom. Teams that quantify cost can prioritize more effectively and defend investment. When reliability is expressed in financial terms, it becomes [more] measurable, comparable, and protectable.

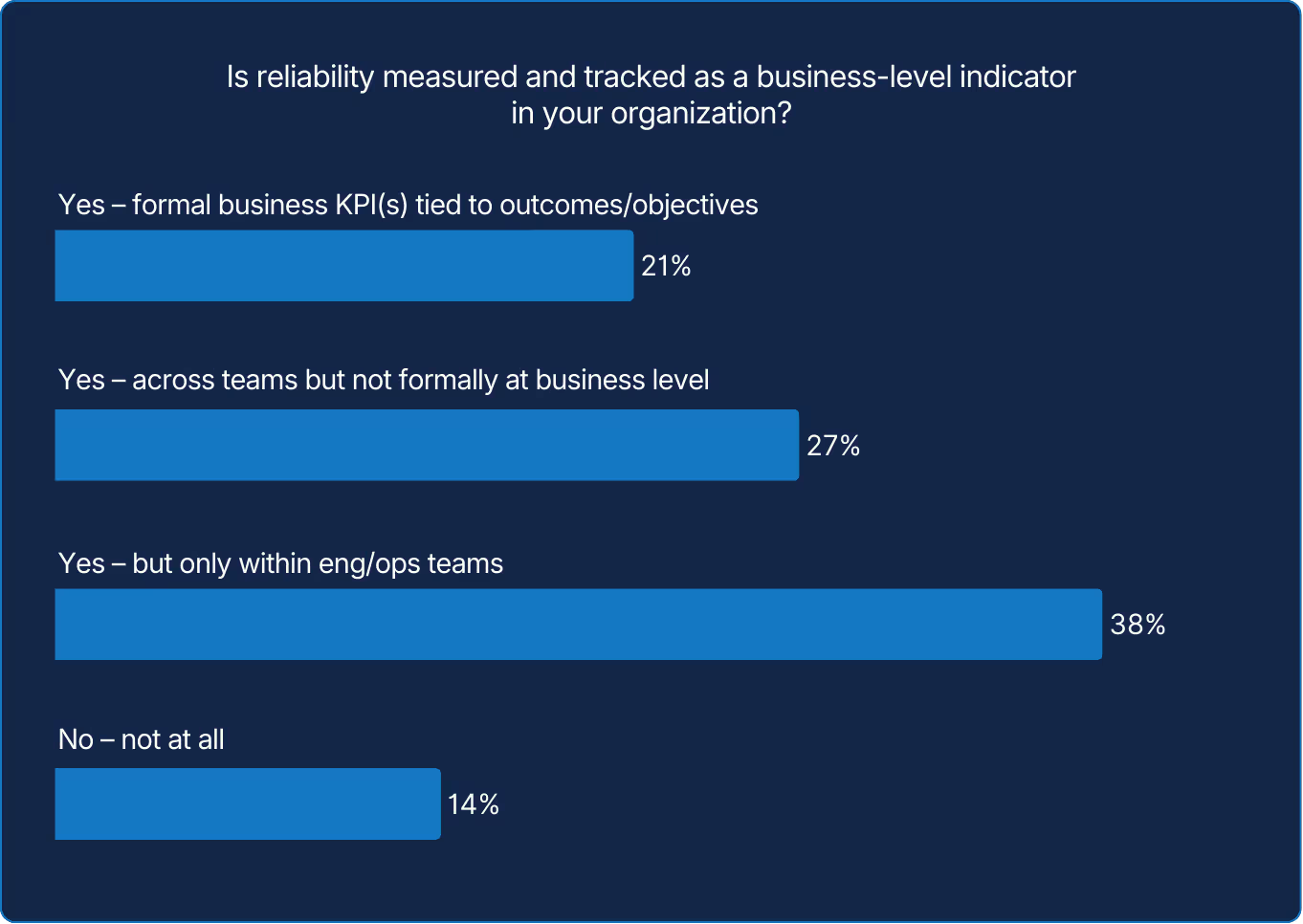

When reliability data stays siloed, it loses influence and visibility. Treating reliability as a shared measure of business health connects uptime and performance to customer trust and revenue. Once reliability appears in business planning cycles, it gains a better chance of being universally understood.

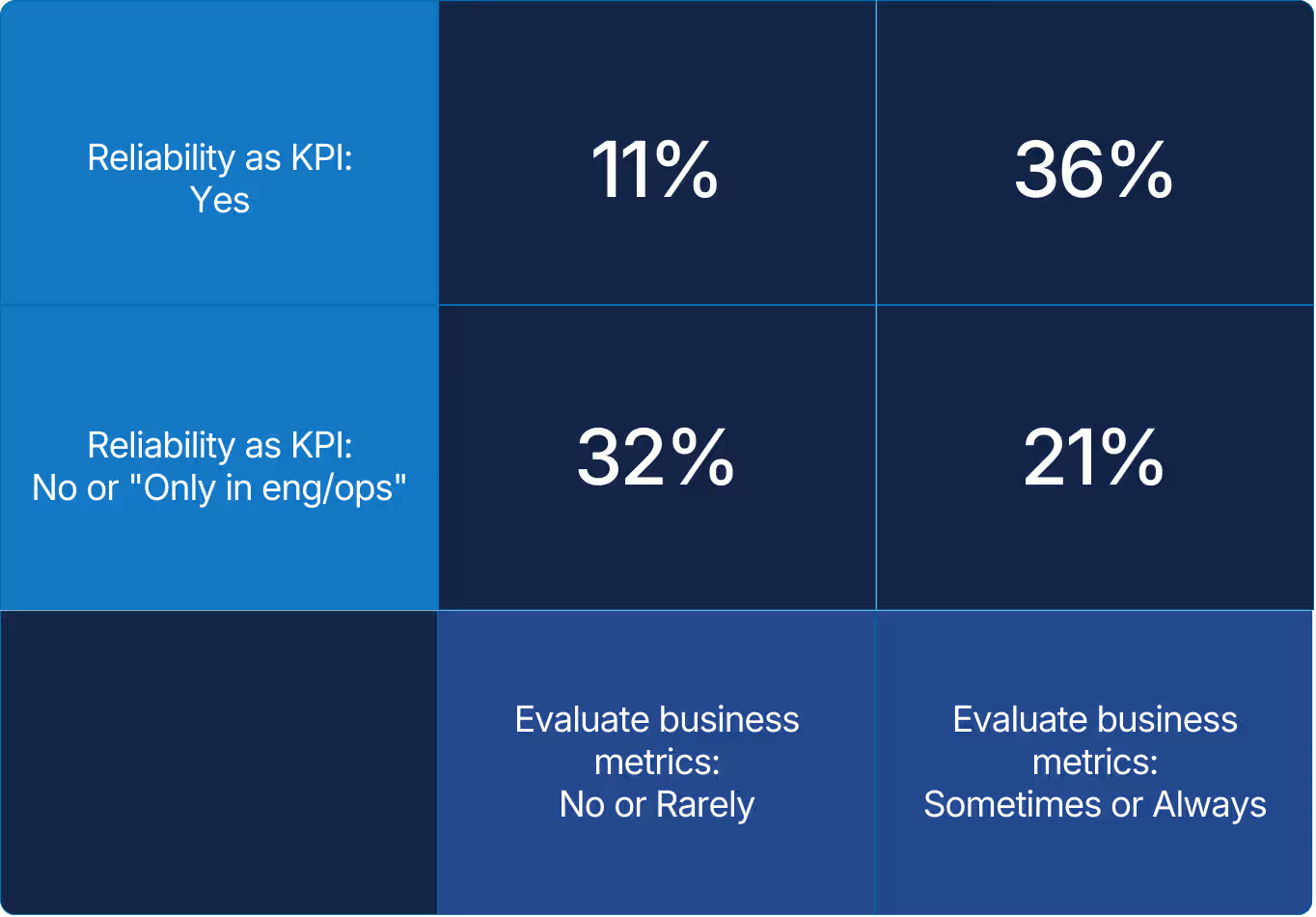

X axis: When your organization improves application performance, do you also evaluate whether business metrics (e.g., NPS or revenue) are affected?

Y axis: Is reliability measured and tracked as a business-level indicator in your organization?

The difference shows what happens when reliability becomes a shared metric. When it’s tracked as a business indicator, alignment improves across teams. However, many still act in silos. Once business leaders and engineers speak the same language, reliability becomes a source of growth rather than a cost center.

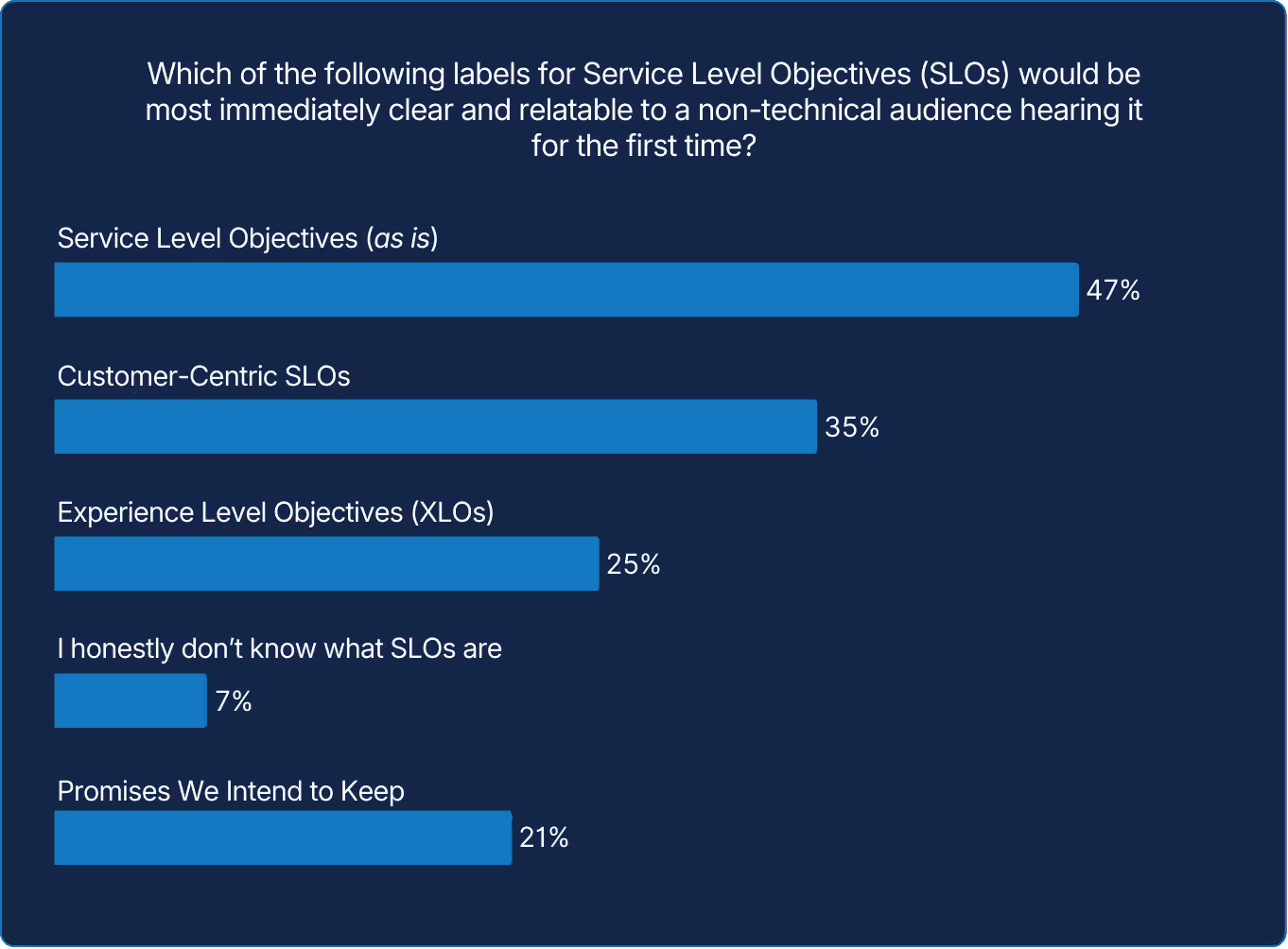

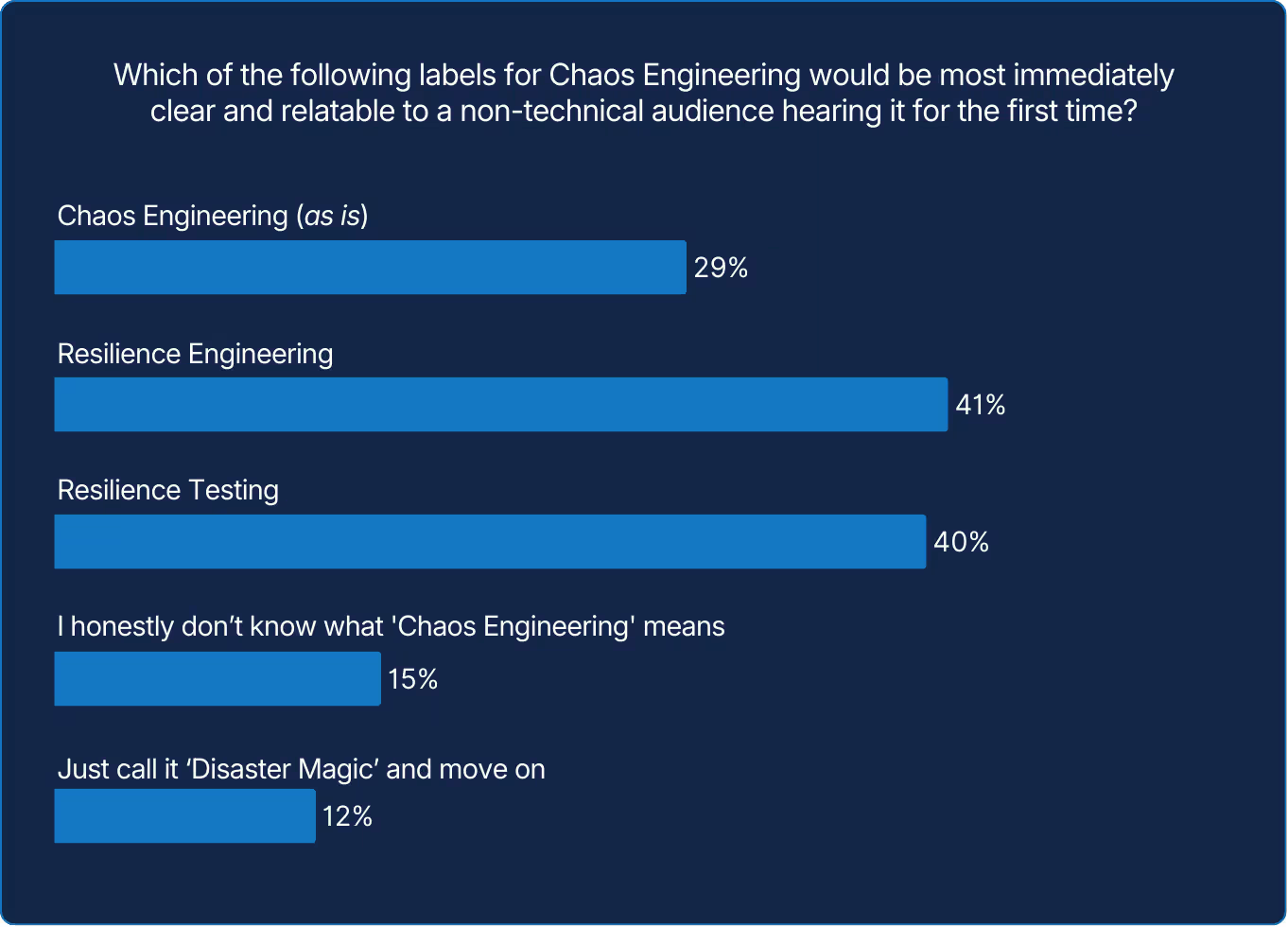

SLO (or similar terms) may be standard terminology within SRE circles, but the technical terminology can leave non-technical audiences in the dark. If reliability is to become a shared business priority, the words used to describe it may matter as much as the metrics themselves.

Reliability has moved from the server room to the boardroom. Around two-thirds of SREs feel alignment with management that performance degradations are as serious as downtime.

This is a clear sign that reliability is no longer defined by uptime but by experience. Users experience both responsiveness and immediacy; perceived speed often defines their judgment. Speed is now one of reliability’s clearest trust signals, and should be a cornerstone of any modern digital business strategy.

Still, awareness isn’t alignment. Only a quarter of organizations consistently evaluate whether application performance improvements affect business metrics like NPS or revenue. Teams that link reliability to outcomes are turning it from an operational task into a competitive advantage in the business of being fast.

That advantage grows when it carries cost. Just one in four organizations formally models the financial impact of incidents, yet those that do give reliability a voice in strategy. Quantifying delay reframes performance as protection of both trust and profit.

Communicating these concepts is still a work in progress. Nearly half would convey “Service Level Objectives,” as is, but many chose “Customer-Centric SLOs” or “Experience Level Objectives.” A few even joked with “Promises We Intend to Keep,” a humorous reminder that reliability is ultimately a promise built on speed, clarity, and credibility.

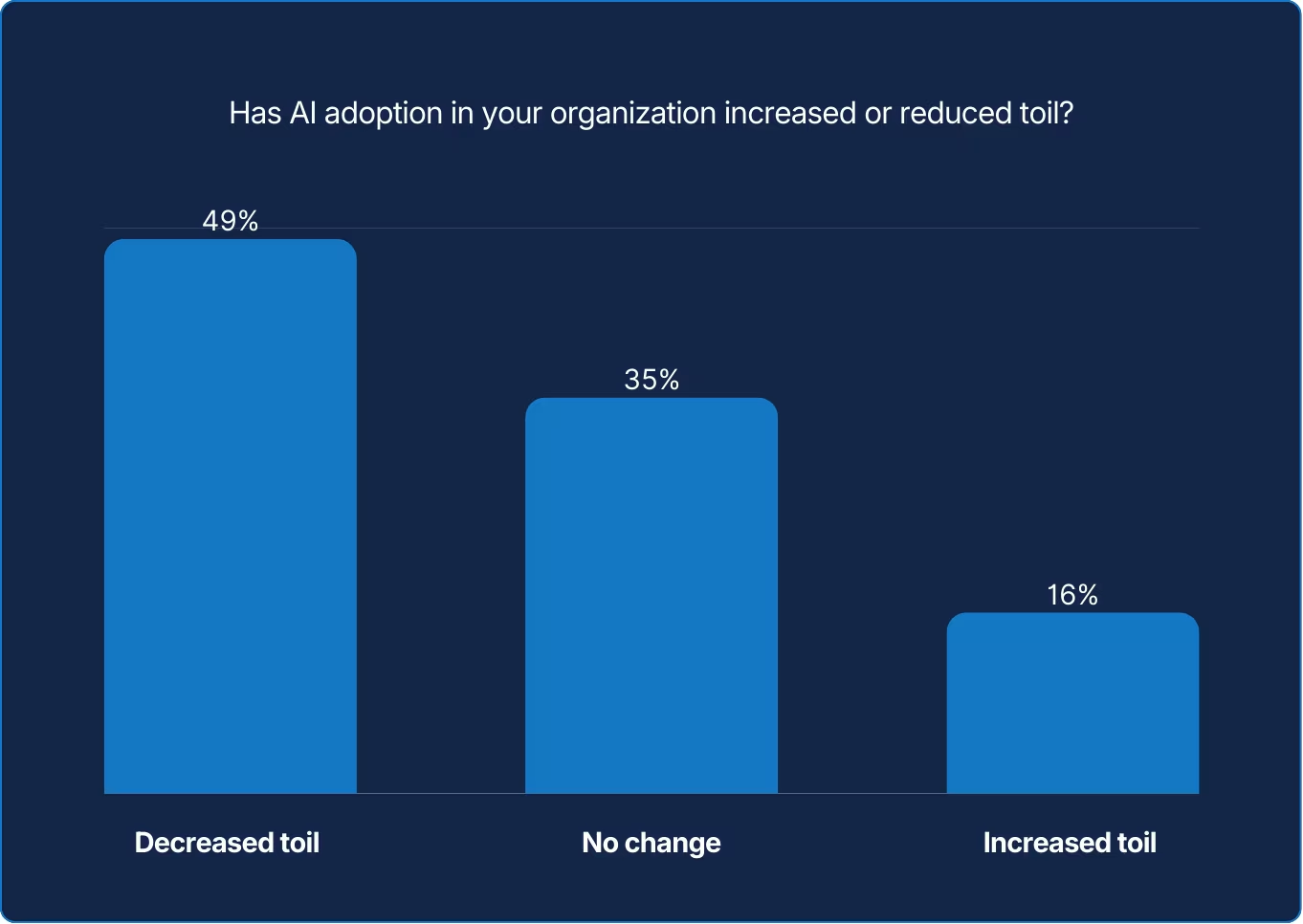

AI promises relief from repetitive work, but its real impact on toil is mixed and evolving.

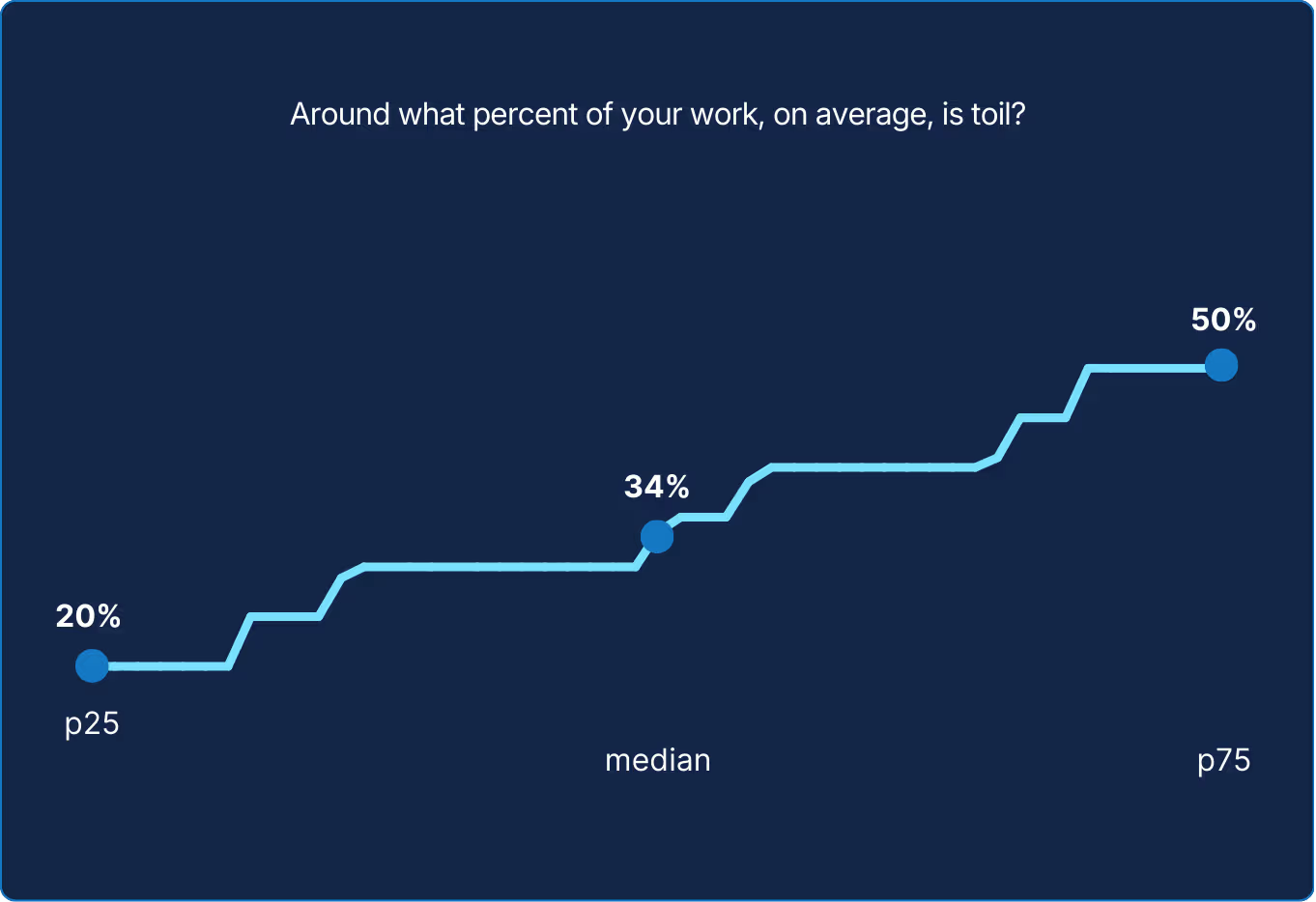

You can’t improve what you can’t see. Measuring toil, no matter how roughly, gives teams a place to start. The numbers might be crude or incomplete, but they offer a necessary baseline for deciding where time, energy, and automation should be applied next.

AI does not remove toil automatically; it redistributes it. The outcome depends on where and how it is applied. Automation can lighten routine load, but maintaining, validating, and explaining AI decisions adds its own layer of effort, reminding teams that efficiency is rarely a zero-sum outcome.

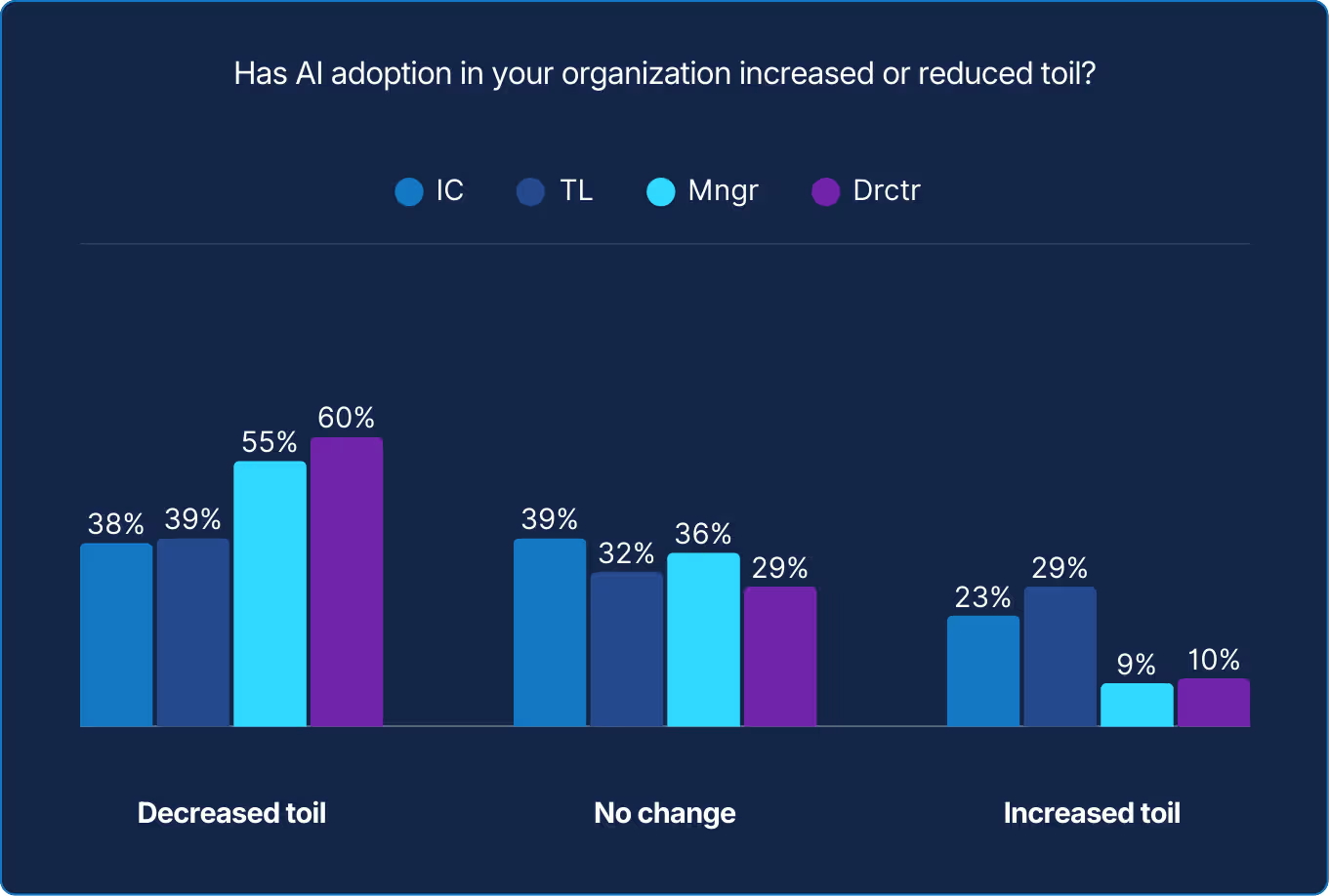

For some practitioners, AI can feel like added complexity, introducing new tools and expectations. For management, it registers as progress. Both perspectives hold truth, just at different resolutions. Until AI reduces friction at the keyboard, its impact will remain more visible in reports than in routines.

Editor’s note: IC refers to individual contributor. TL refers to team lead (or simply lead), Mngr refers to manager, and Drctr refers to director. Through the report Practitioners refers to IC and TL as a group. Management refers to managers and directors as a group.

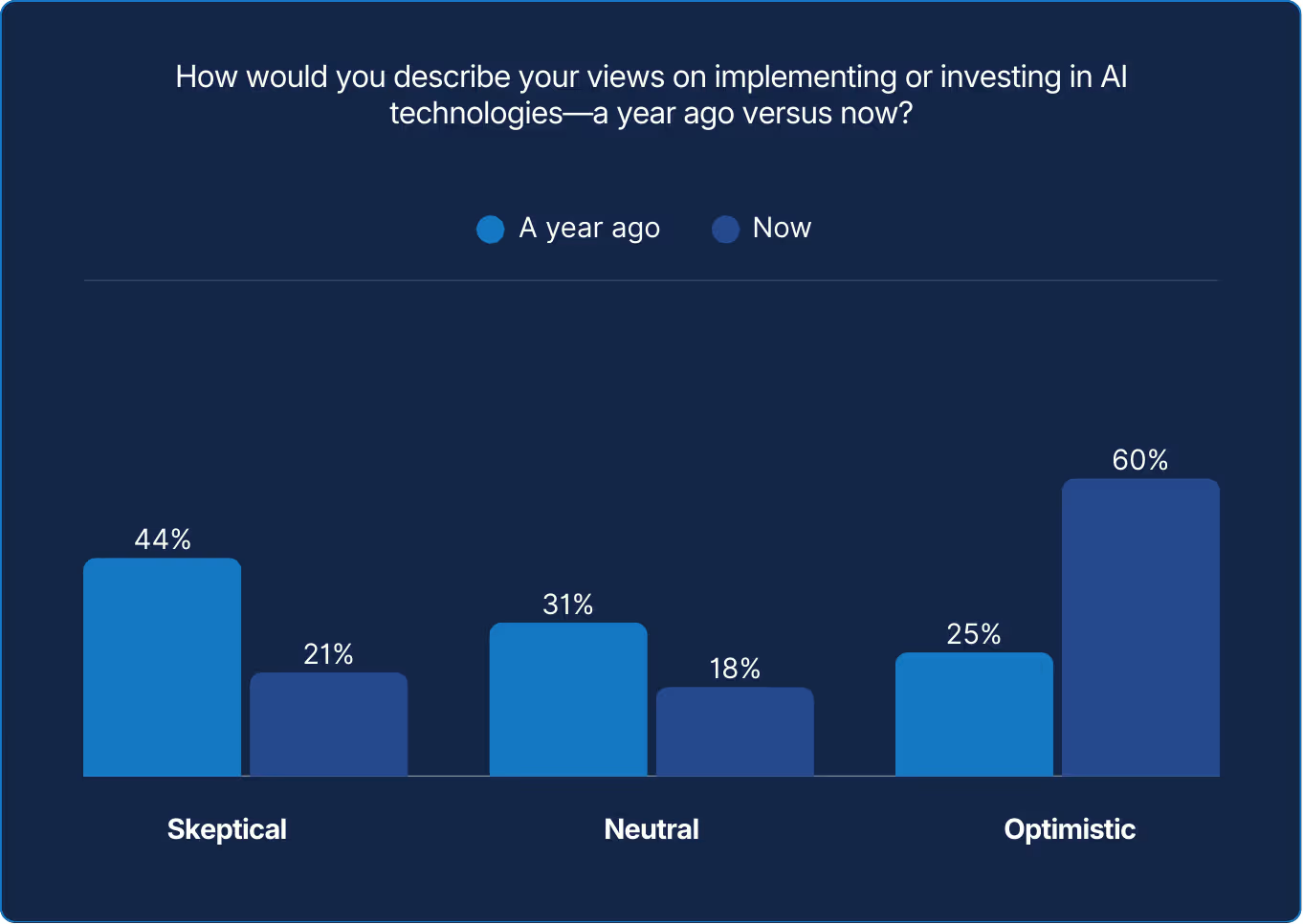

As a directional trend, sentiment around AI has turned a corner, moving from skepticism to optimism. But “AI technologies” is an umbrella term. Its value and relevance depend on how it’s applied. The key is focus: define the problem with precision, then identify the AI capabilities that directly serve that purpose. And that purpose must, or at least should, come from an IT-to-business aligned conversation. Without that alignment, AI becomes just another shiny object.

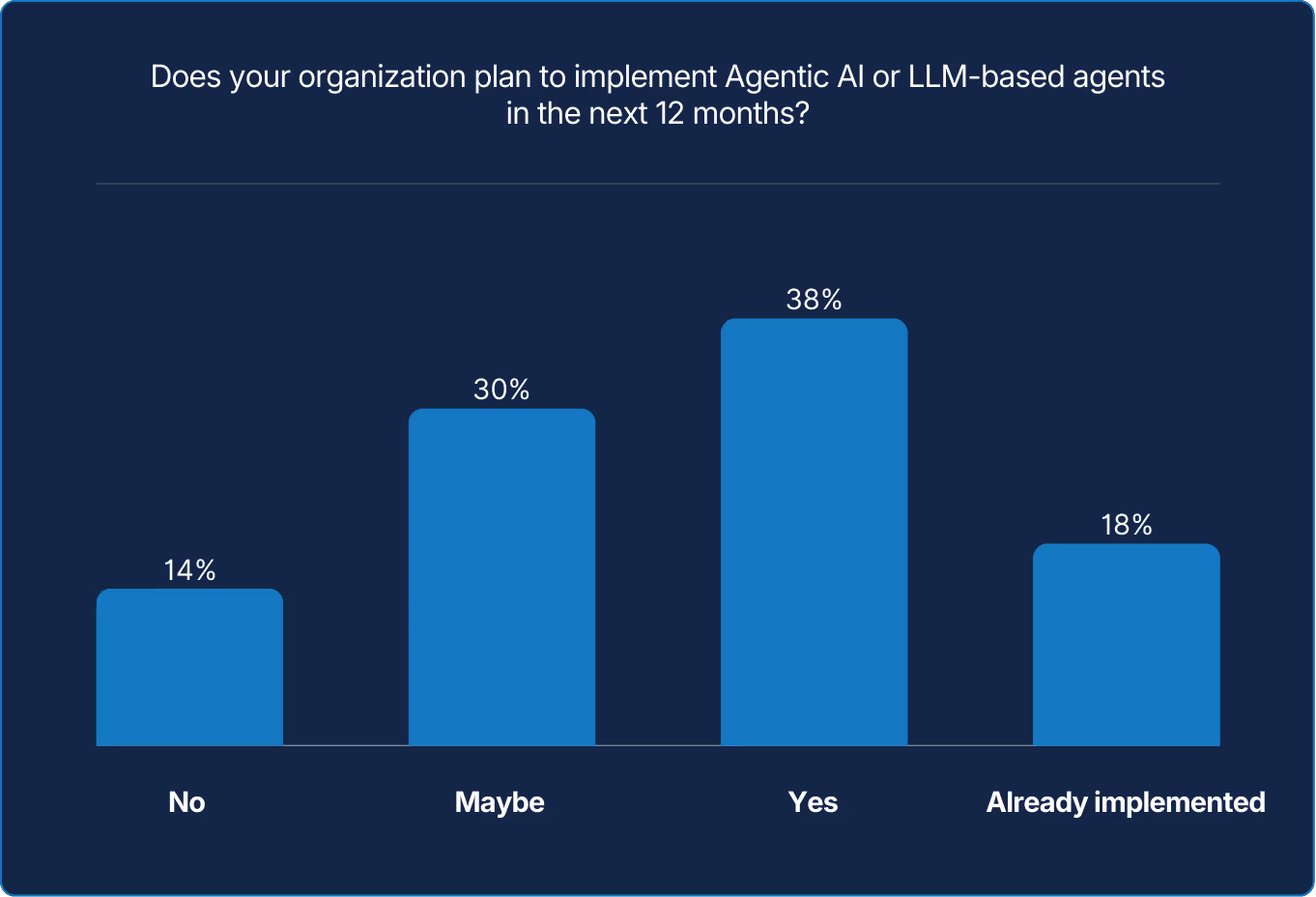

Intent is rapidly becoming action. Experimentation with LLMs is evolving into broad adoption, as teams move beyond curiosity to real commitment. The next challenge is proving that AI agents can reliably deliver sustained business value, not just technical novelty.

X axis: Does your organization plan to implement Agentic AI or LLM-based agents in the next 12 months?

Y axis: How would you describe your current views on implementing or investing in AI technologies?*

*Neutral views 7%, 10% not displayed

Optimistic views on AI align closely with plans or actions around agentic systems, forming the largest segment of the quadrant (top right). Thecause for this relationship isn’t determinable from the data; it’s a bit like the chicken or the egg. Still, it’s easy to imagine the two feeding each other: belief creates action, and action builds belief. Momentum, once started, tends to sustain itself.

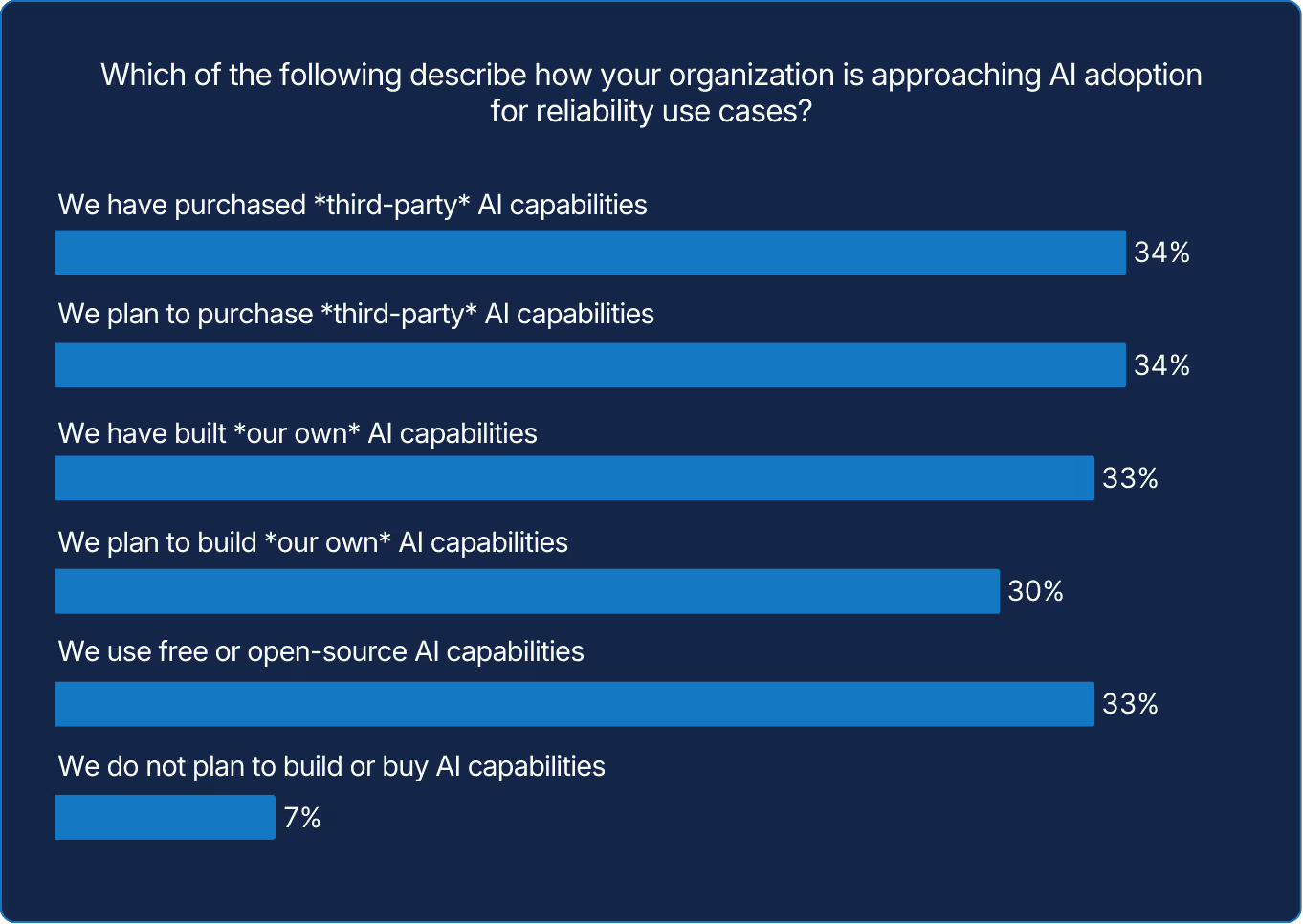

There’s no single path to AI adoption for reliability use cases. Teams seem to be trying different approaches depending on their context. We believe this variety is driven by AI’s relative novelty, which is why it’s important to be cautious about any claims of “best practices” for adopting AI in reliability contexts.

Reliability has always depended on human endurance to patch, watch, and repeat. But endurance doesn’t scale, and the SRE profession knows it.

For years, toil has been reliability’s tax: the repetitive work that keeps systems alive but slows innovation to a crawl. Now, AI is changing the economics of effort. For the first time, automation isn’t just scripting tasks. It’s interpreting, correlating, and deciding.

The data shows cautious optimism taking root. Most SREs report modest reductions in toil. Leaders report even greater gains, highlighting a difference in perspective. Those closest to the code still feel the friction of implementation, while management see the efficiency at scale. The trend indicated by the data suggests that AI is starting to reduce some repetitive work in the reliability stack, though experiences vary. What started as tool-assisted triage is evolving into decision-assisted engineering.

Attitudes toward AI have matured in parallel. Last year’s skepticism is giving way to structured experimentation. Nearly four in ten organizations plan to deploy LLM-driven or agentic systems within the year, led overwhelmingly by those who already believe in the technology’s promise. Optimism, it turns out, is a performance multiplier.

AI isn’t replacing reliability engineers; it is augmenting their ability to act so they can focus higher-value work. The emerging reliability practice is hybrid, combining human judgment with automated systems that learn over time.

Resilience doesn’t emerge from stability. It is earned through the courage to test, fail, and learn on purpose.

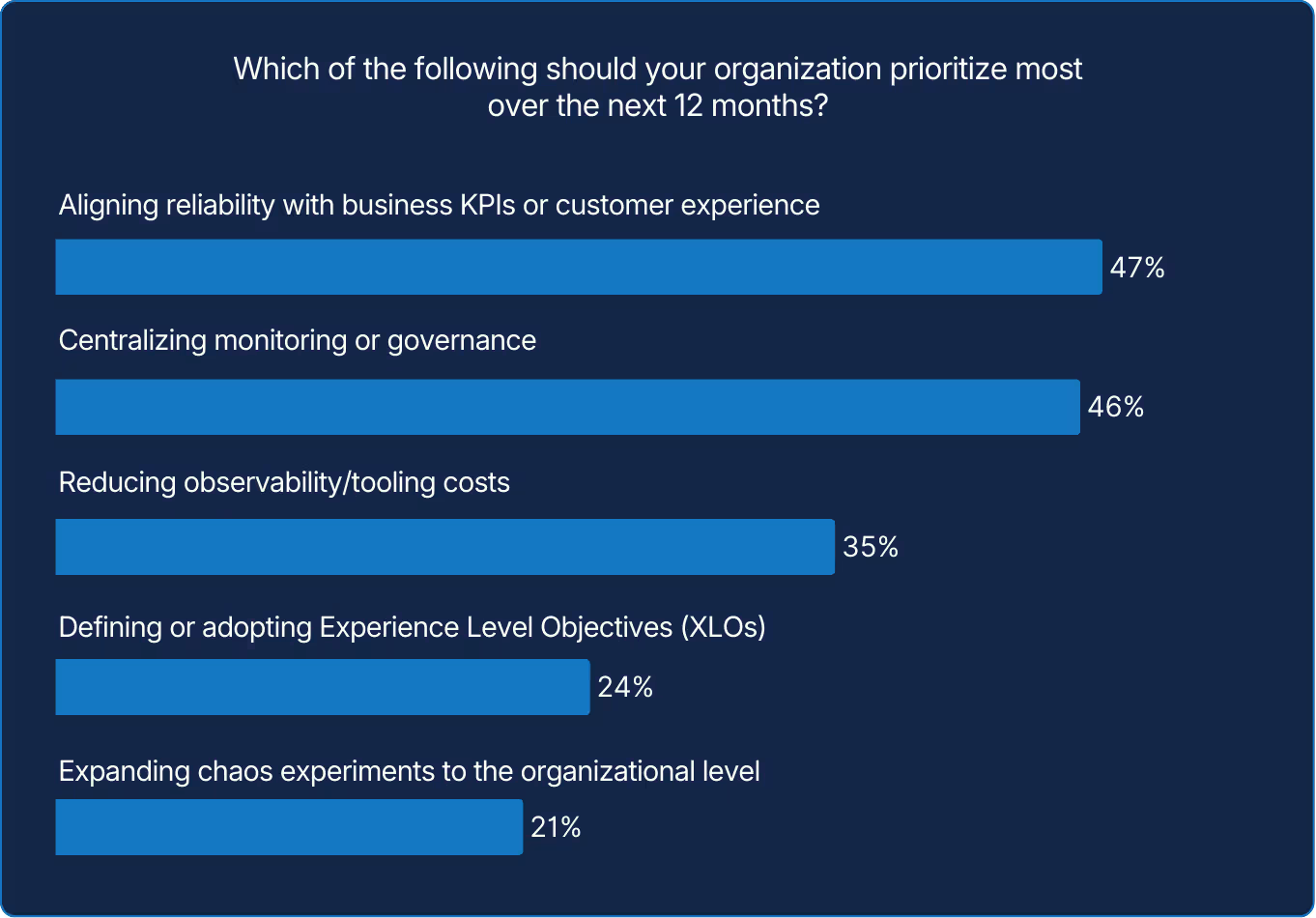

This year's research indicates a desire to move from an operational goal to a business strategy. Trust is no longer earned through uptime alone but through alignment with measurable outcomes. The year ahead will test how reliability connects outcomes for customers and measurable value for business.

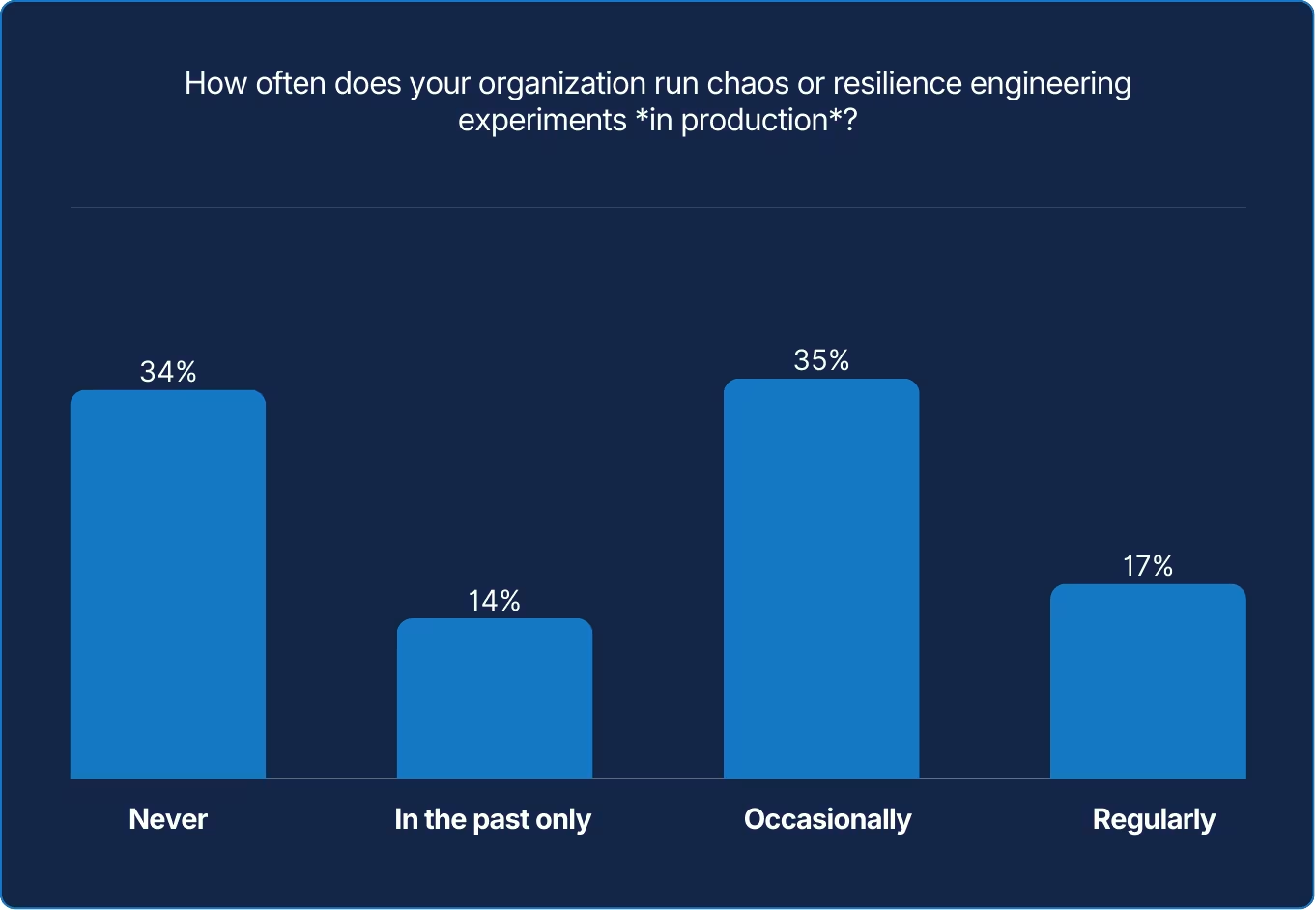

Teams may believe that resilience must be practiced, yet many hesitate to test failure where it matters most. Controlled experiments turn uncertainty into insight by exposing weak points before the world does. Every organization claims to value resilience, but only those that practice it deliberately, in controlled conditions, actually build it.

Teams still treat failure as something to prevent rather than explore. Avoiding turbulence can feel safe, but it slows learning. Reliability grows stronger when exposed, not when insulated. Teams that break what they build prepare for the rigors of the untamed internet, and controlled experimentation is how they do it.

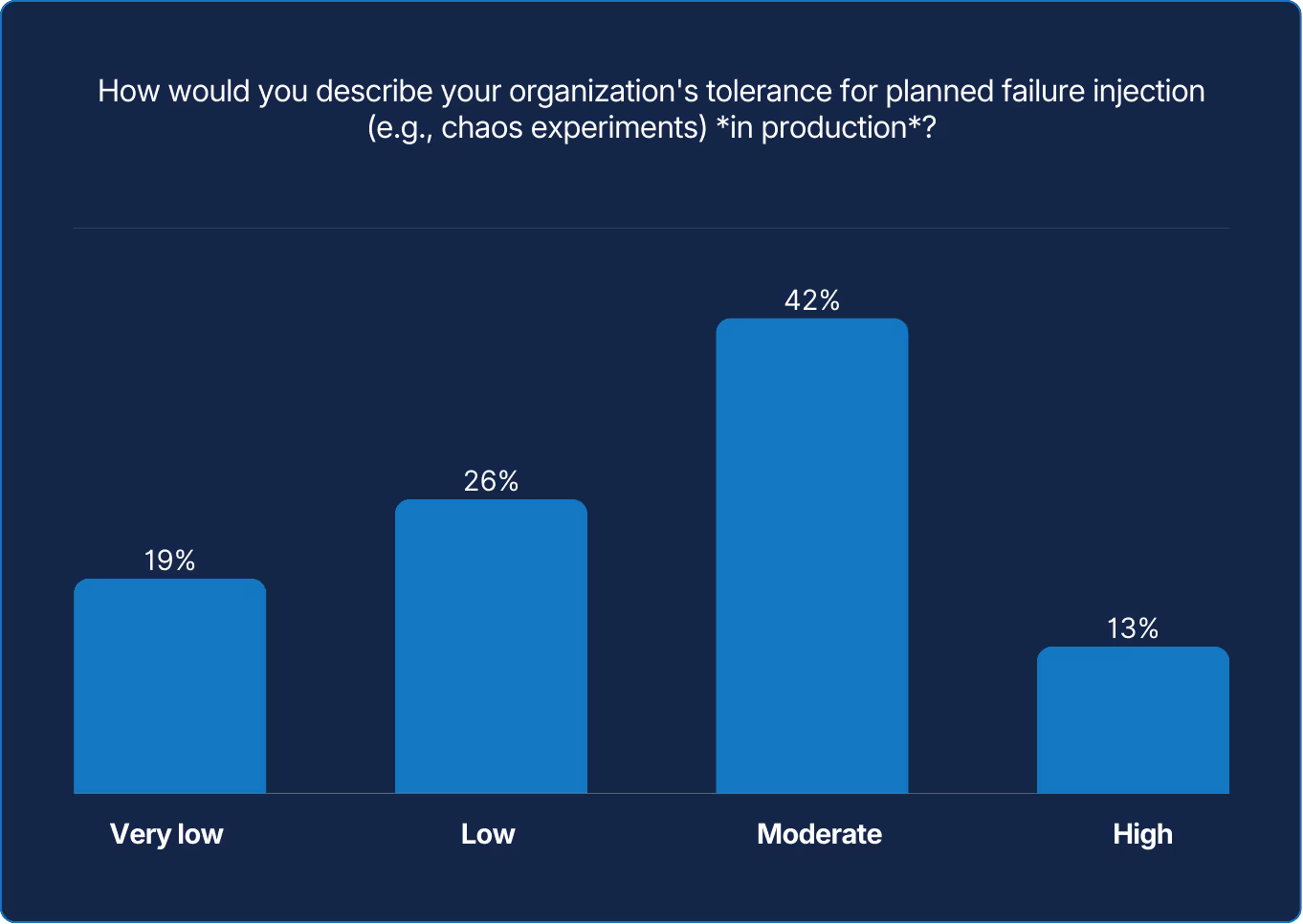

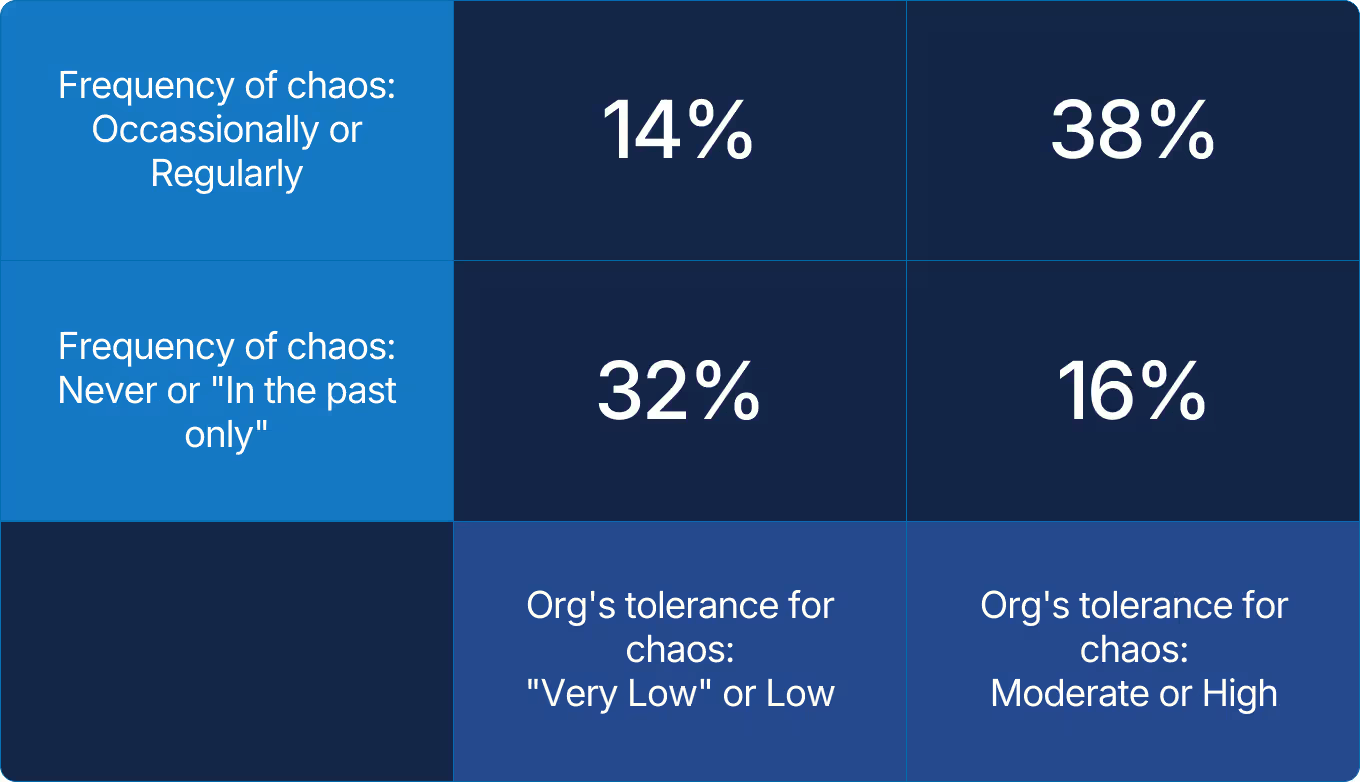

X axis: How would you describe your organization's tolerance for planned failure injection (e.g., chaos experiments) in production?

Y axis: How often does your organization run chaos or resilience engineering experiments in production?

Two groups stand out: those that practice chaos engineering and have support for it, and those that do neither. This suggests to us two reinforcing loops, one virtuous, one limiting. In the first, confidence fuels practice and practice builds confidence. In the second, hesitation reinforces itself, leaving teams untested and uncertain. Reliability grows in one loop and erodes in the other.

Reliability concepts that are approachable and repeatable may [hopefully] help increase adoption and business investment. But language matters as much as practice. When reliability is framed through words that invite understanding rather than mystique, it becomes easier for organizations to rally behind it. Replacing “chaos” with “resilience” may be one example. Words set tone, and tone determines whether reliability work is seen as threatening versus beneficial.

Reliability isn’t just about keeping the lights on. It’s about proving they’ll stay on when the storm hits. Yet most organizations still hesitate to test that truth in production.

While interest in resilience engineering is growing, only a minority are bold enough to inject failure where it truly matters: the live environment. Nearly half of respondents report a low tolerance for planned failure, constrained by e.g., risk aversion, legacy systems, and other factors. Too many teams rehearse it reactively instead of proactively.

Among those who do (rehearse it proactively), a culture grounded in confidence, not caution, emerges. These teams see chaos experiments not as recklessness, but as rehearsal. Their mindset is that it’s better to break on purpose than to break by surprise. Controlled failure exposes weaknesses that uptime dashboards can’t. Each test builds foresight, trust, and adaptability before the next real incident arrives.

This reflects a growing reliability divide. Some teams measure stability retrospectively, while others engineer foresight through deliberate failure testing. The latter are discovering that deliberate disruption strengthens more than systems. It strengthens people. When failure is expected and intentionally explored, teams can respond faster, learn more effectively, and reduce fear around experimentation.

The frontier of reliability belongs to those willing to test what they depend on. Courage, after all, is the ultimate resilience.

Reliability isn’t a stack; it’s a strategy. AI delivers the most value when core signals are unified, governed, and designed to work together.

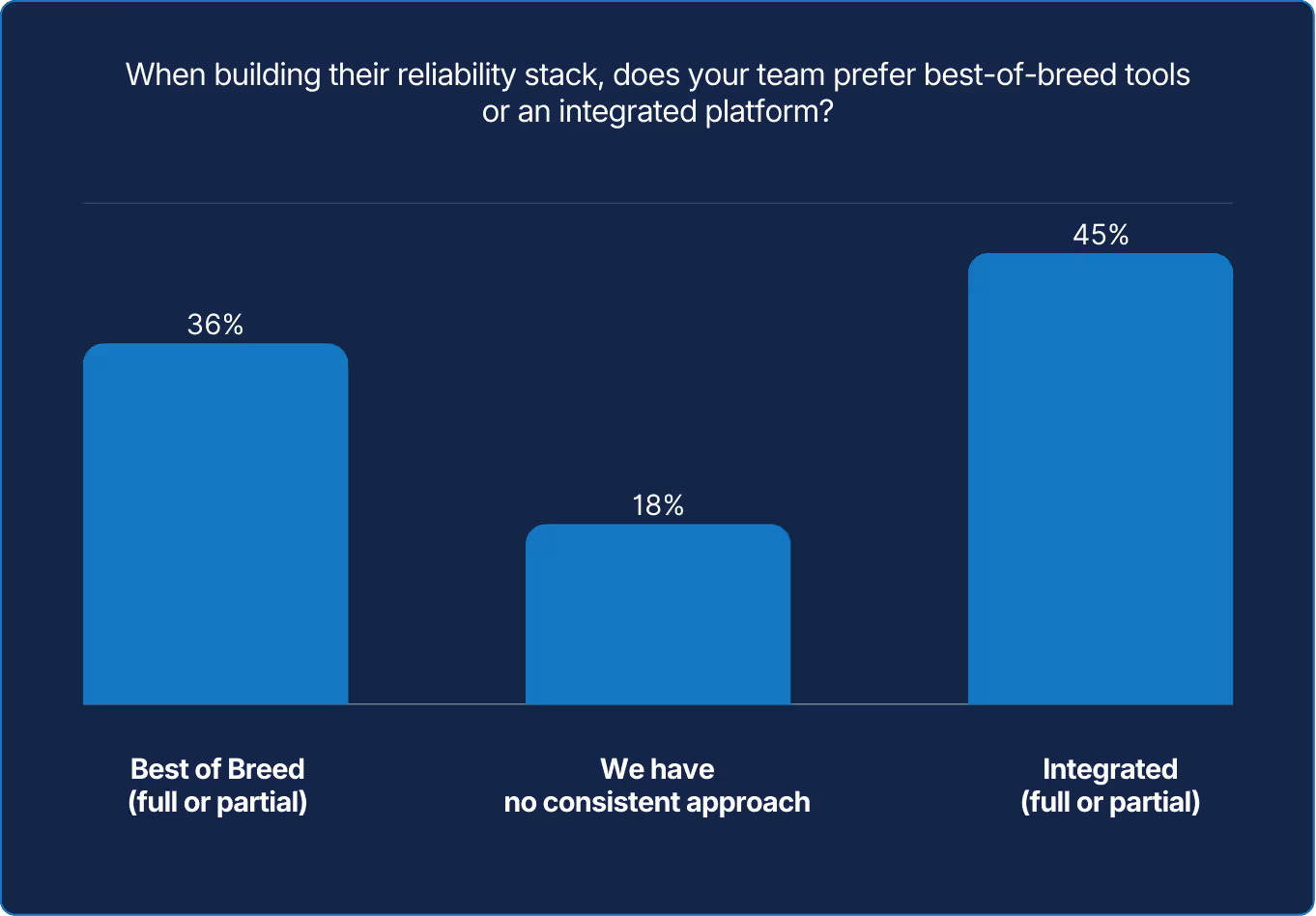

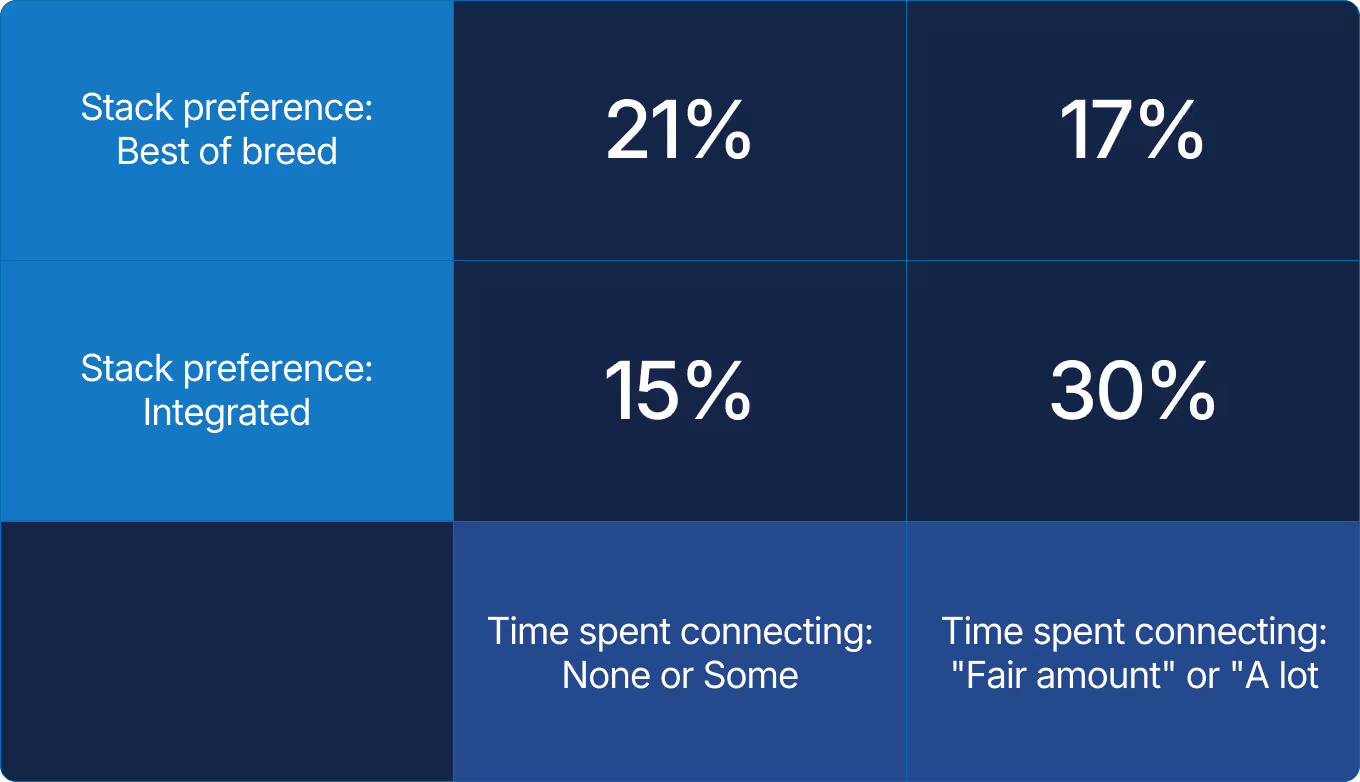

Preferences for best-of-breed or integrated platforms are nearly balanced, with 18% reporting no fixed approach. Both approaches can work, but as environments and teams scale, many organizations bring more of their core reliability workflows into shared, well-integrated systems.

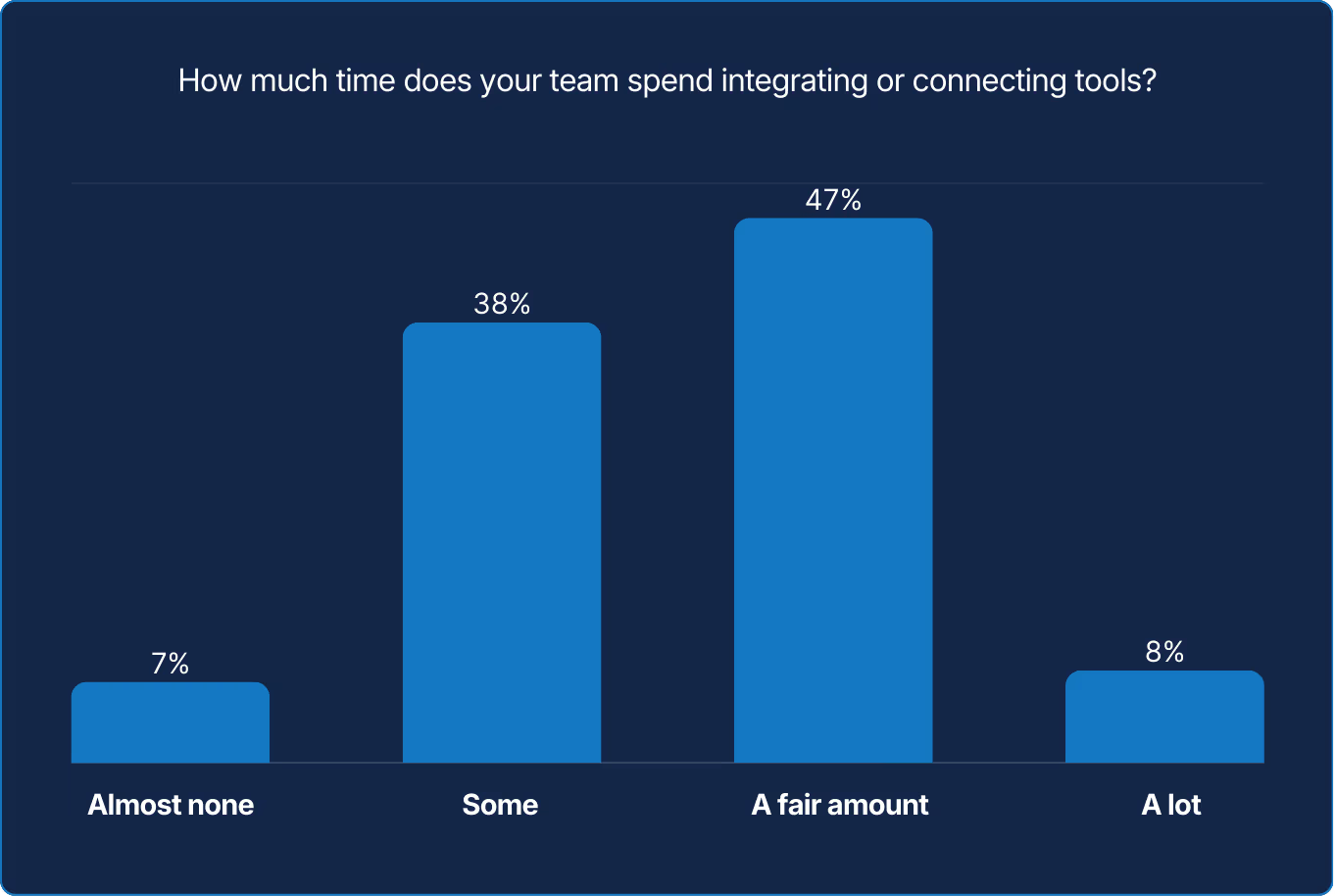

Integration effort is not just an operational detail. It is a signal. When teams spend significant time wiring tools together, it often reflects fragmented data, inconsistent ownership, or unclear boundaries between systems. AI can reduce some of this burden, but its effectiveness depends on the quality and consistency of the underlying foundations. Starting with what matters most to the business helps teams decide where simplification and shared systems create the greatest leverage.

X axis: How much time does your team spend integrating or connecting tools?

Y axis: When building their reliability stack, does your team prefer best-of-breed tools or an integrated platform?

Reliability stacks are not static. They will evolve from ad hoc to orchestrated to consolidated, with specialized tools included when they add clear value. Technology choices create leverage only when they are reinforced by unified foundations that trace directly to business priorities.

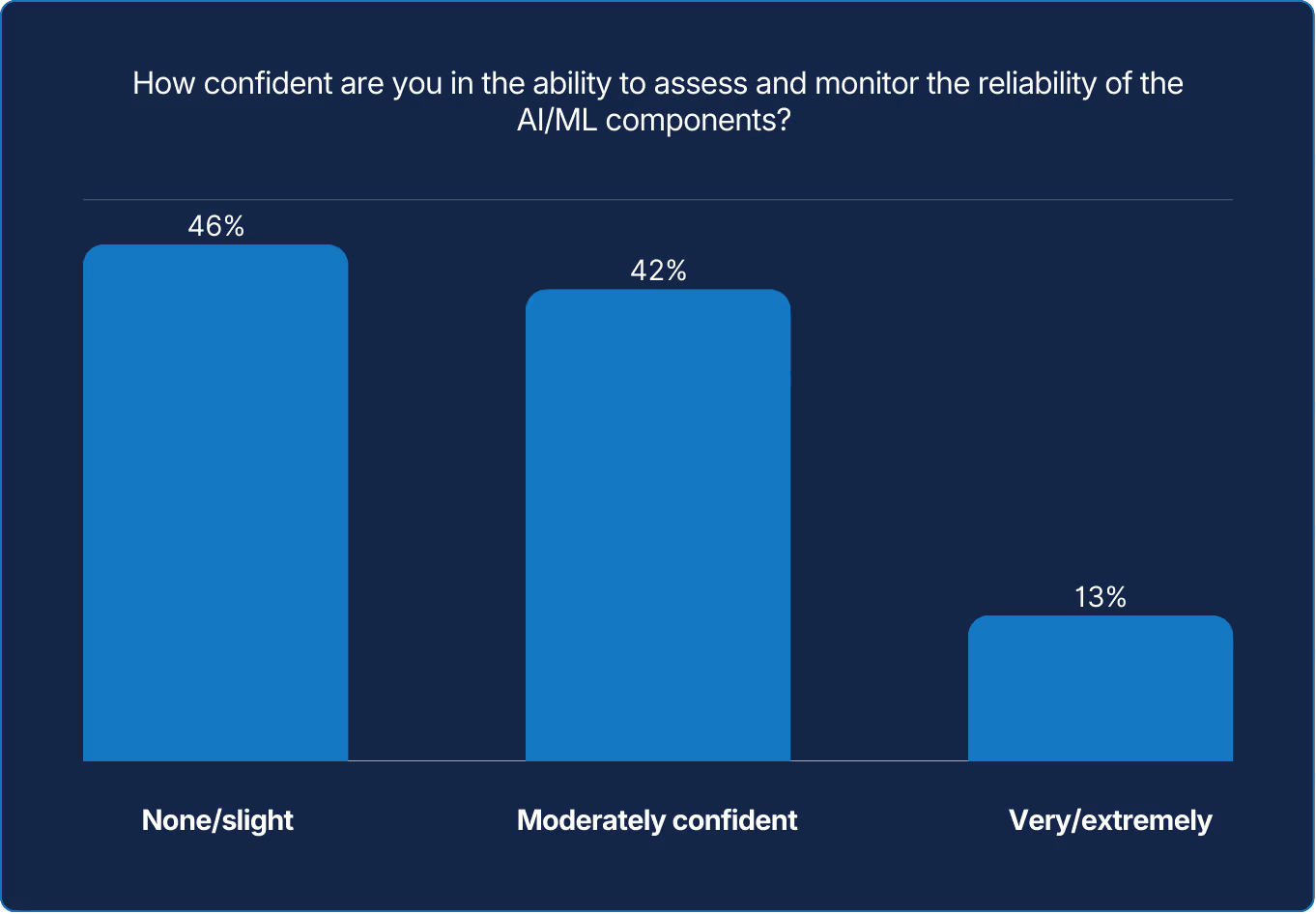

The majority lack confidence in assessing AI/ML reliability, even as these technologies become critical. Building this confidence requires spanning more than just technology. It will require significant team learning in order to manage this new realm.

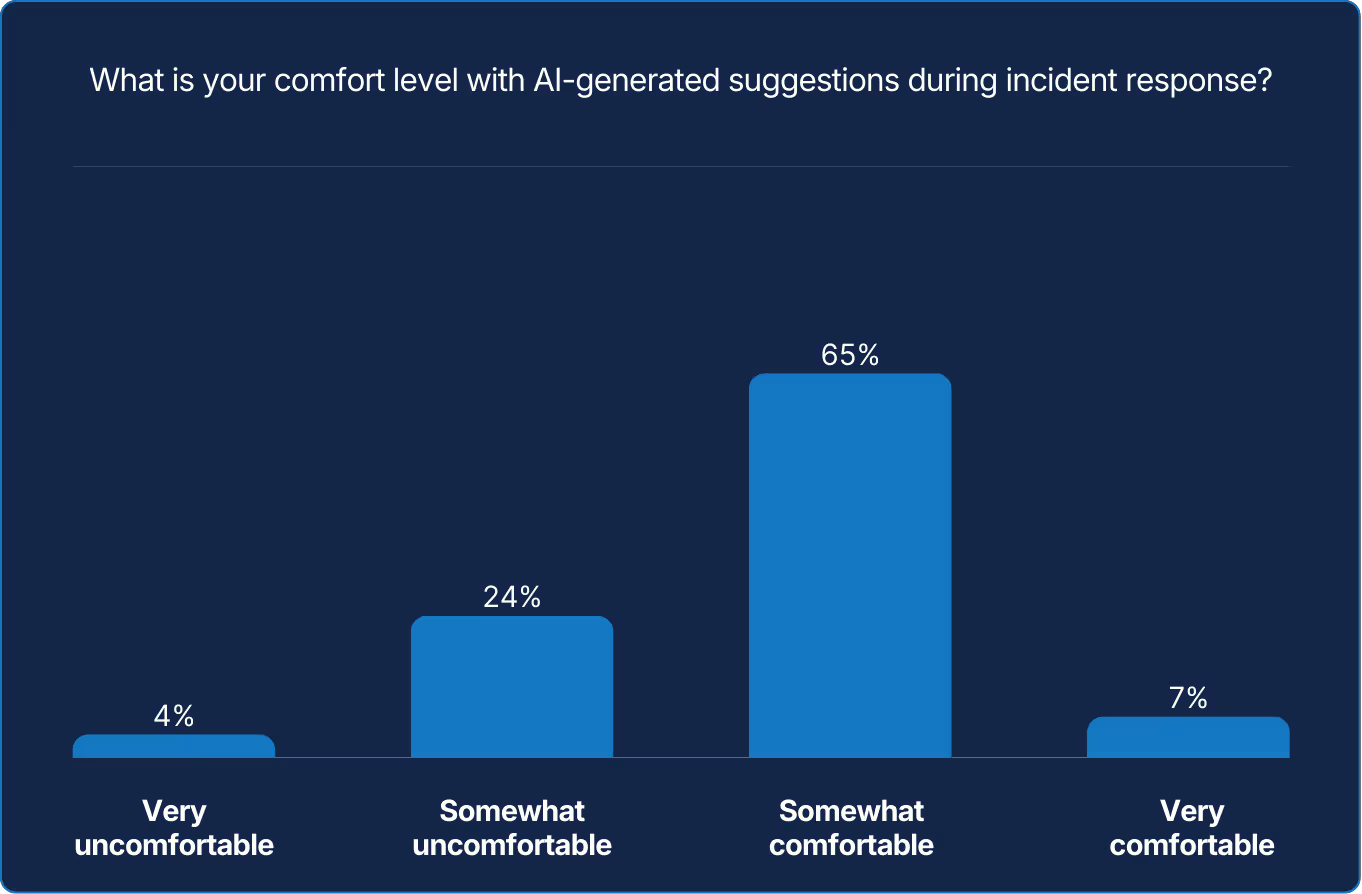

AI can make meaningful contributions but needs carefully scoped requests. Most teams are open to its assistance but remain watchful.

They may be beginning to recognize that the response itself now has added layers. That is, not just reacting to an incident, but at times realizing AI may cause another incident within an incident. Over time, that watchfulness may mature into a new discipline of its own, effectively using AI’s participation to augment the team while avoiding abdication of thought and responsibility.

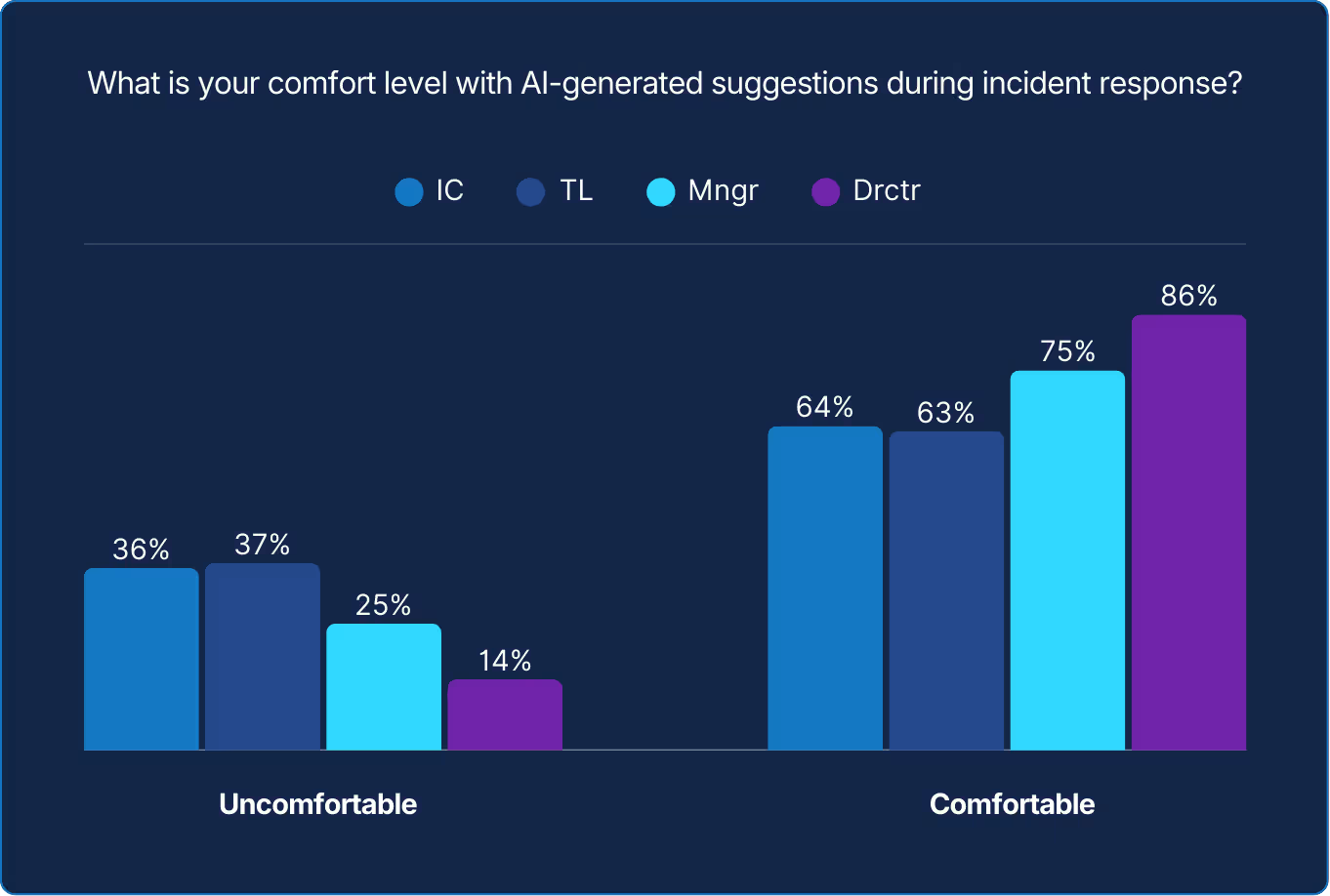

The divide between management and practitioners may be reflective of their distance from day-to-day incidents. For some, comfort level with AI could stem from detachment. For others, comfort level with AI could stem from close proximity. However, so as not to stereotype or “box in” by rank, distance from incidents is just one possible reason for the opposing trends.

Reliability has outgrown its old boundaries. What was once a patchwork of tools now demands a more intentional system, designed for adaptability as complexity and expectations grow

Reliability is no longer defined by individual tools alone, but by how well systems work together. As environments scale, teams are learning that resilience comes less from endlessly stitching parts together and more from establishing shared foundations. Integrated platforms provide consistency and speed, while specialized tools still offer depth where it matters most.

Best-of-breed remains a valid strategy when applied deliberately. It reflects a belief that excellence is distributed and that innovation often comes from specialization. But without common data models, governance, and context, even the best tools can introduce friction. Mature teams increasingly focus on reducing fragmentation at the core so that reliability work compounds rather than competes.

AI now plays a critical role in this shift, not by hiding complexity, but by amplifying clarity.

When AI operates on consistent, high-qualiy signals, it can correlate events, enrich context, and automate decisions that once consumed engineering time. Where data is fragmented, AI spends more effort reconciling noise than producing insight.

This is the intelligence of integration: designing systems that make sense together. The modern reliability stack is not defined by fewer tools, but by more coherent ones. Progress comes not from eliminating complexity outright, but from organizing it around shared intent, visibility, and trust.

The organizations leading this shift don’t see AI as a shortcut or a substitute for sound architecture. They see it as an amplifier of well-designed systems. The future of reliability depends less on managing more tools and more on building foundations that allow intelligence, automation, and human judgment to work in concert.

Your systems are only as reliable as your people are allowed to grow.

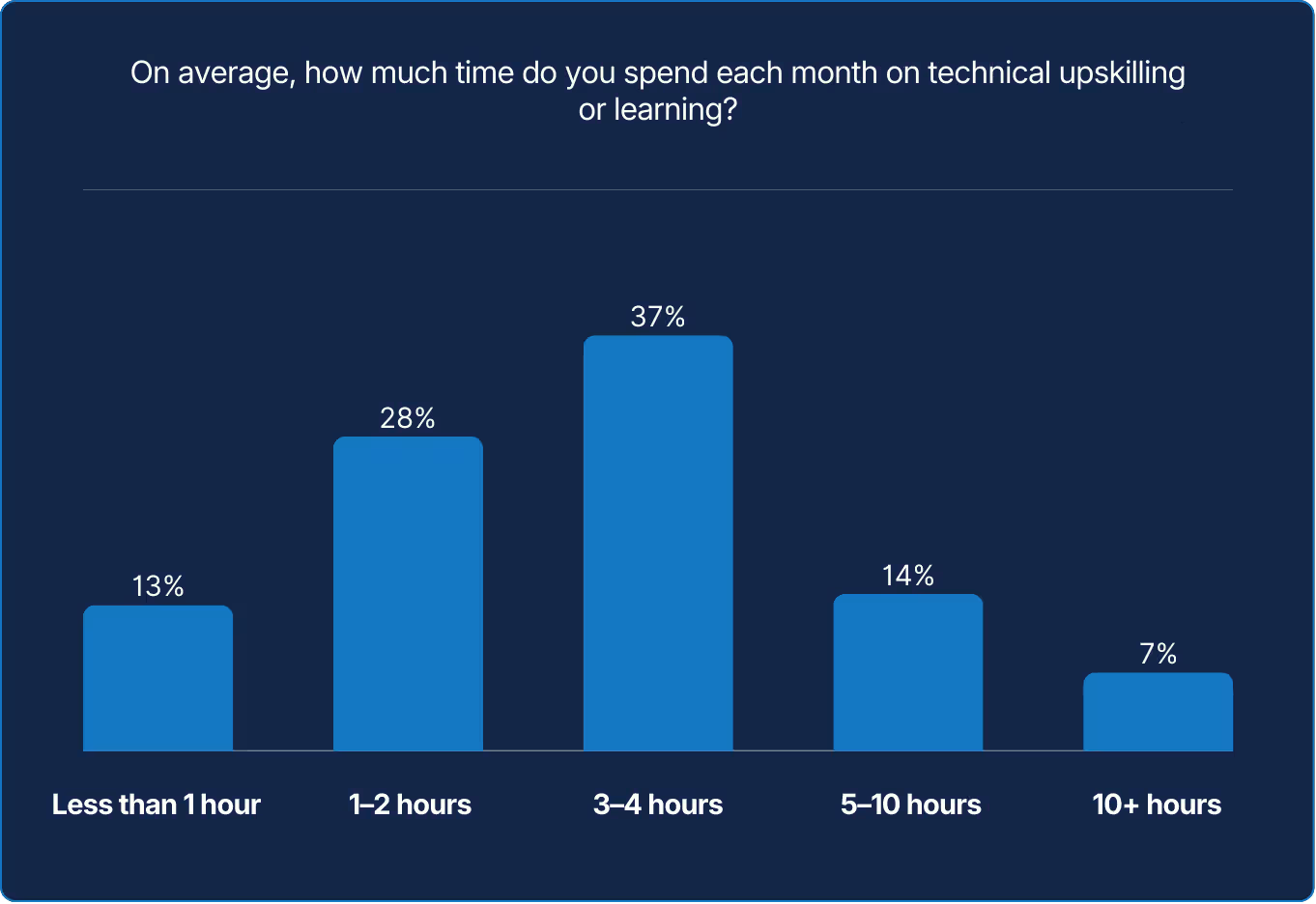

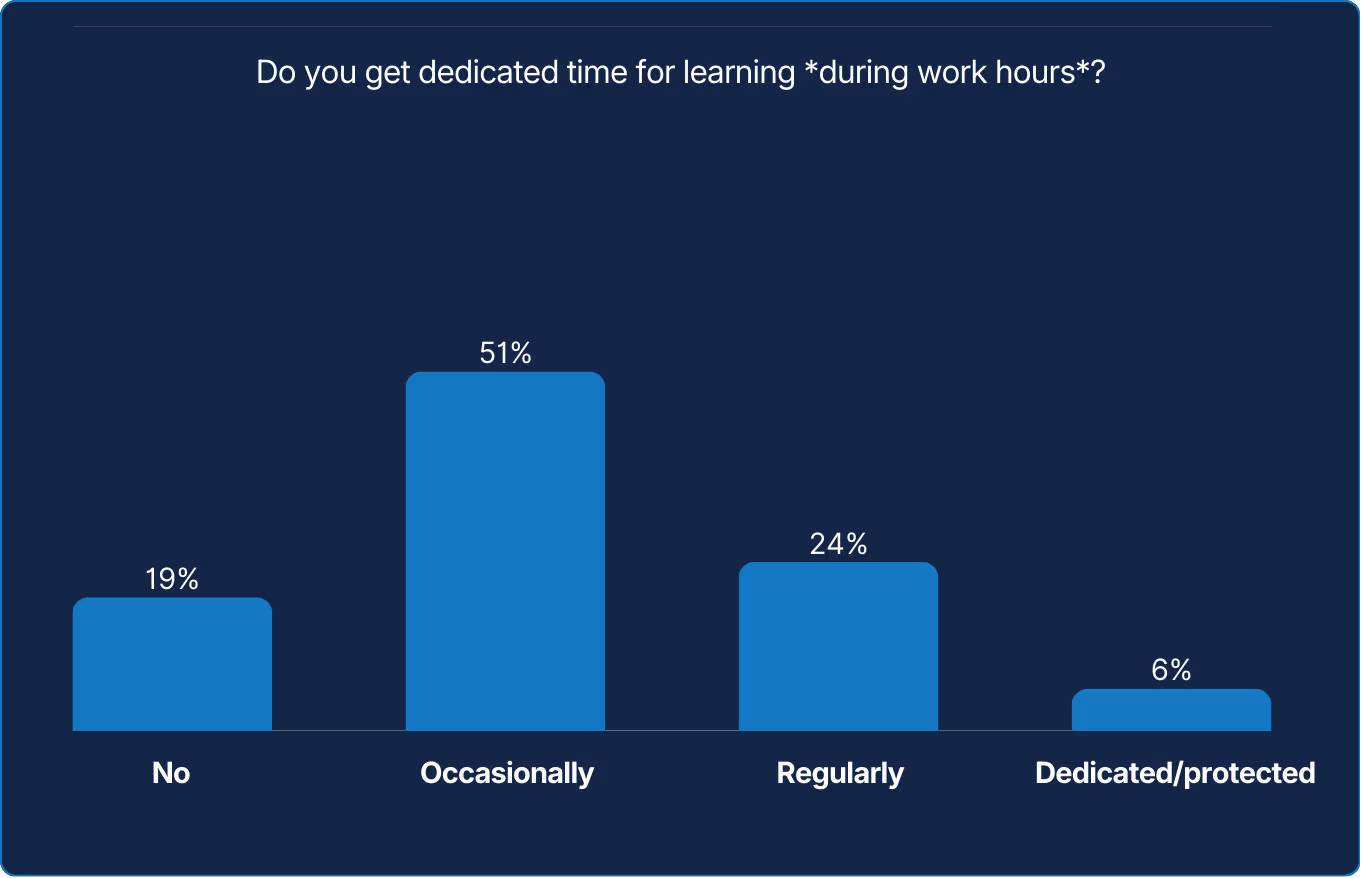

The data paints a picture of a workforce caught between intent and capacity. Curiosity exists; time does not. Reliability depends on people learning, as much as systems. The ability to learn continuously may now define resilience as clearly as uptime once did.

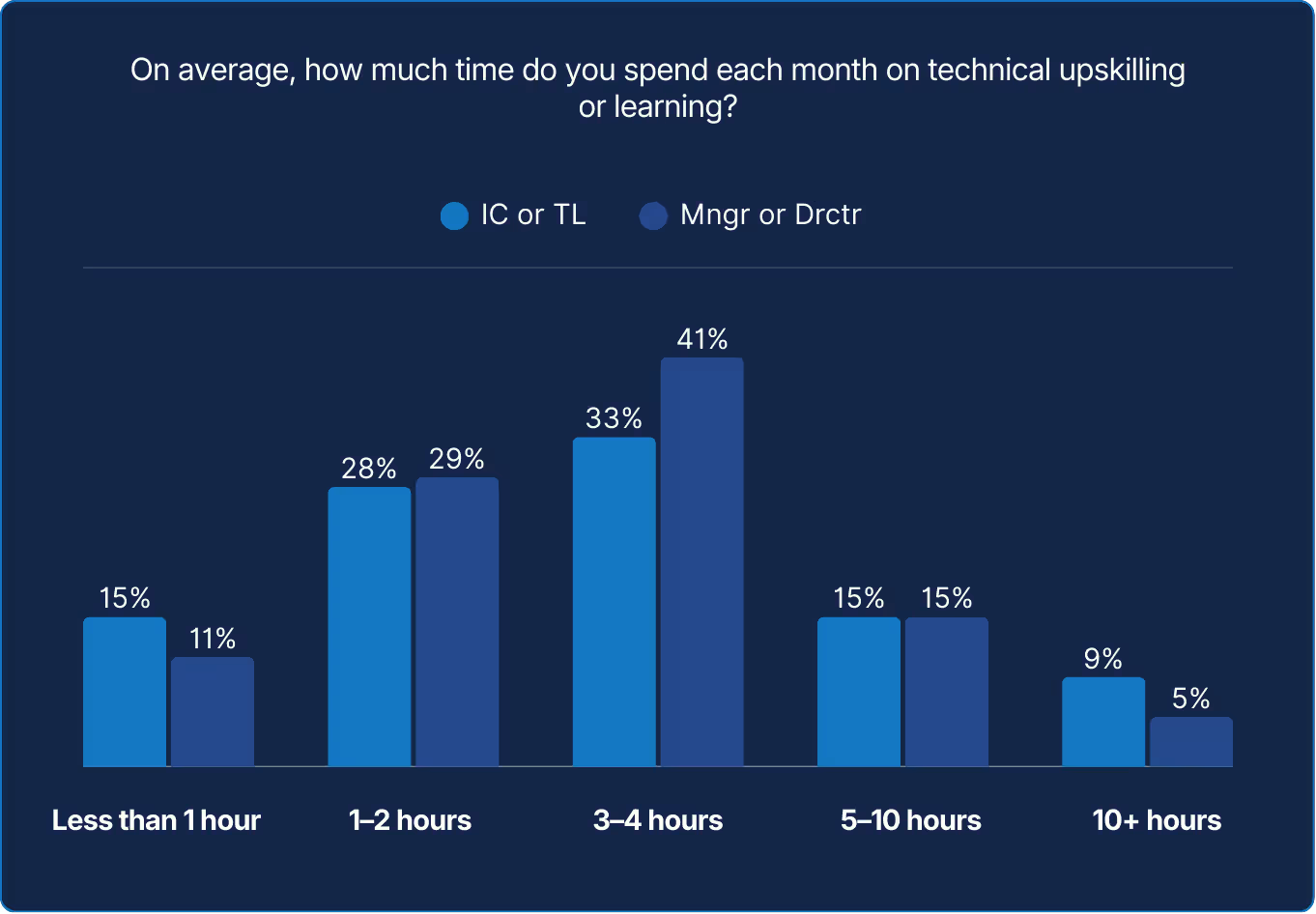

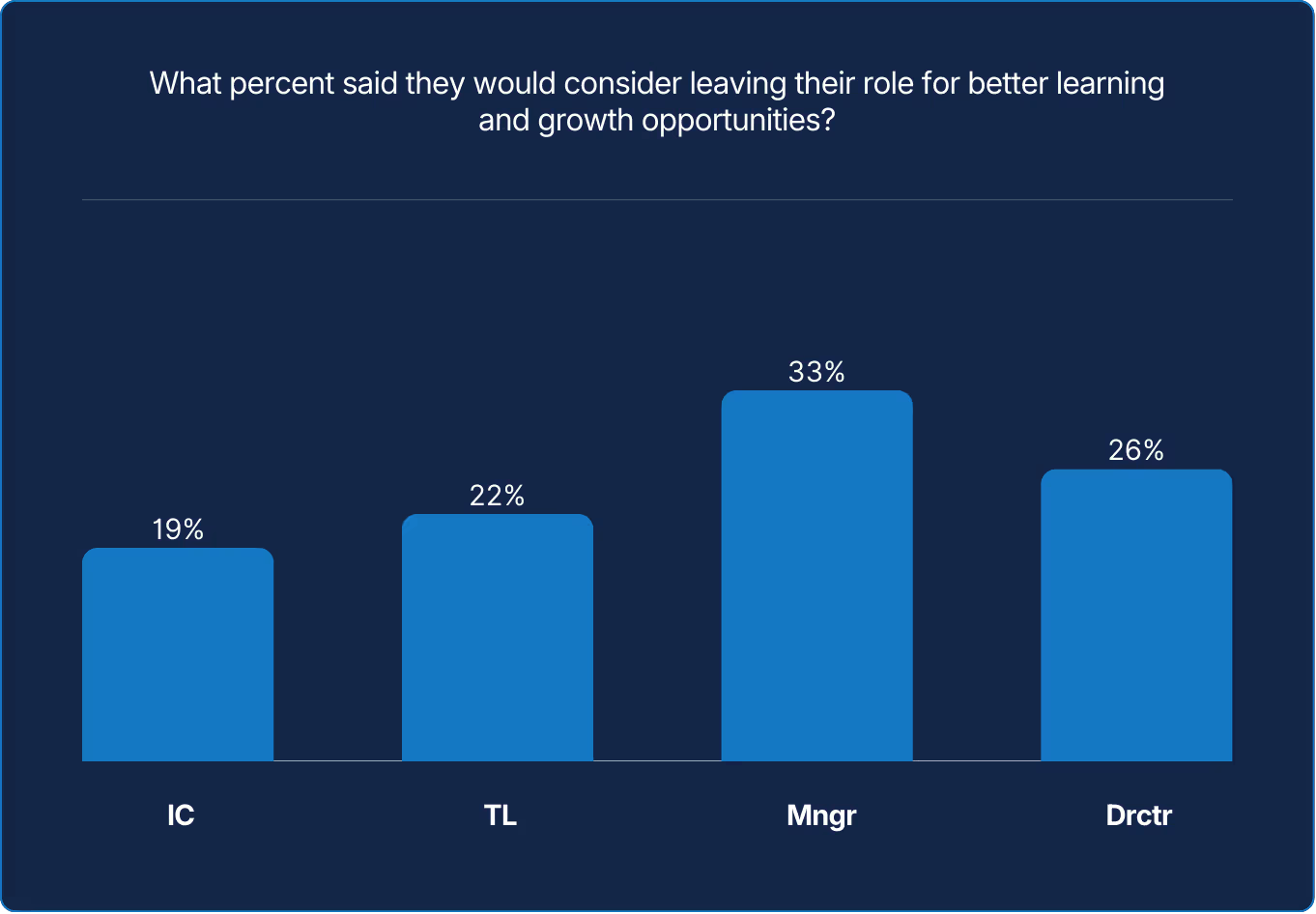

The survey data suggests management ‘buys’ perspective and, apparently, learning time. Yet those who could use it most remain stretched thin. Until time to grow is treated as integral to reliability work, progression will depend more on circumstance than on culture.

Organizations often praise learning more than they fund it. Yet the most reliable systems are built by engineers whose curiosity is part of the job, not an afterthought. Time is the real training budget. Teams that weave learning into daily work preserve both capability and engagement.

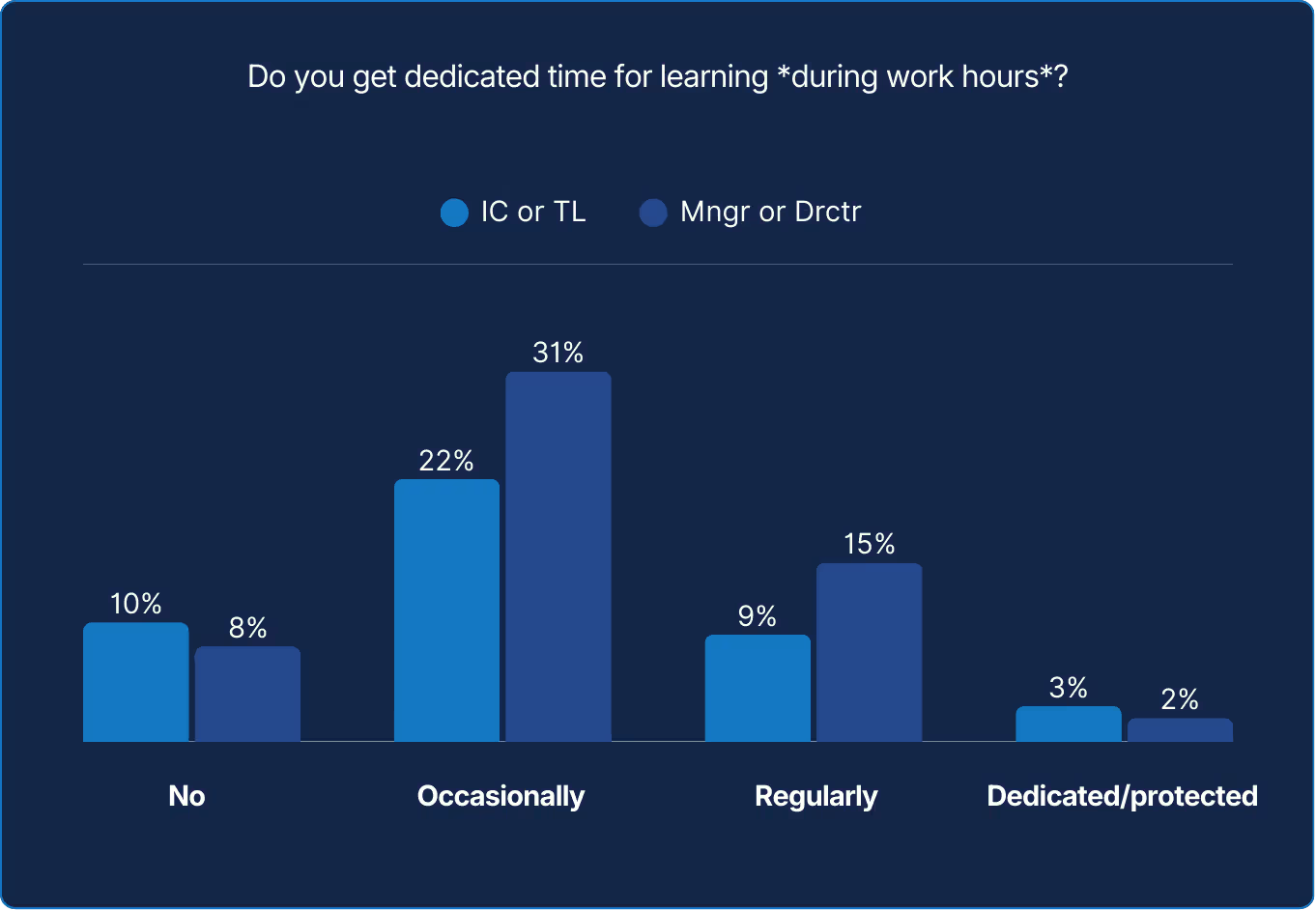

Access to learning grows with authority, not with need. Managers and directors are more likely to schedule learning time, while very few call it protected. Culture may applaud curiosity, yet calendars often cancel it. Until learning is engineered into the workflow, growth will remain optional for many and uneven for all.

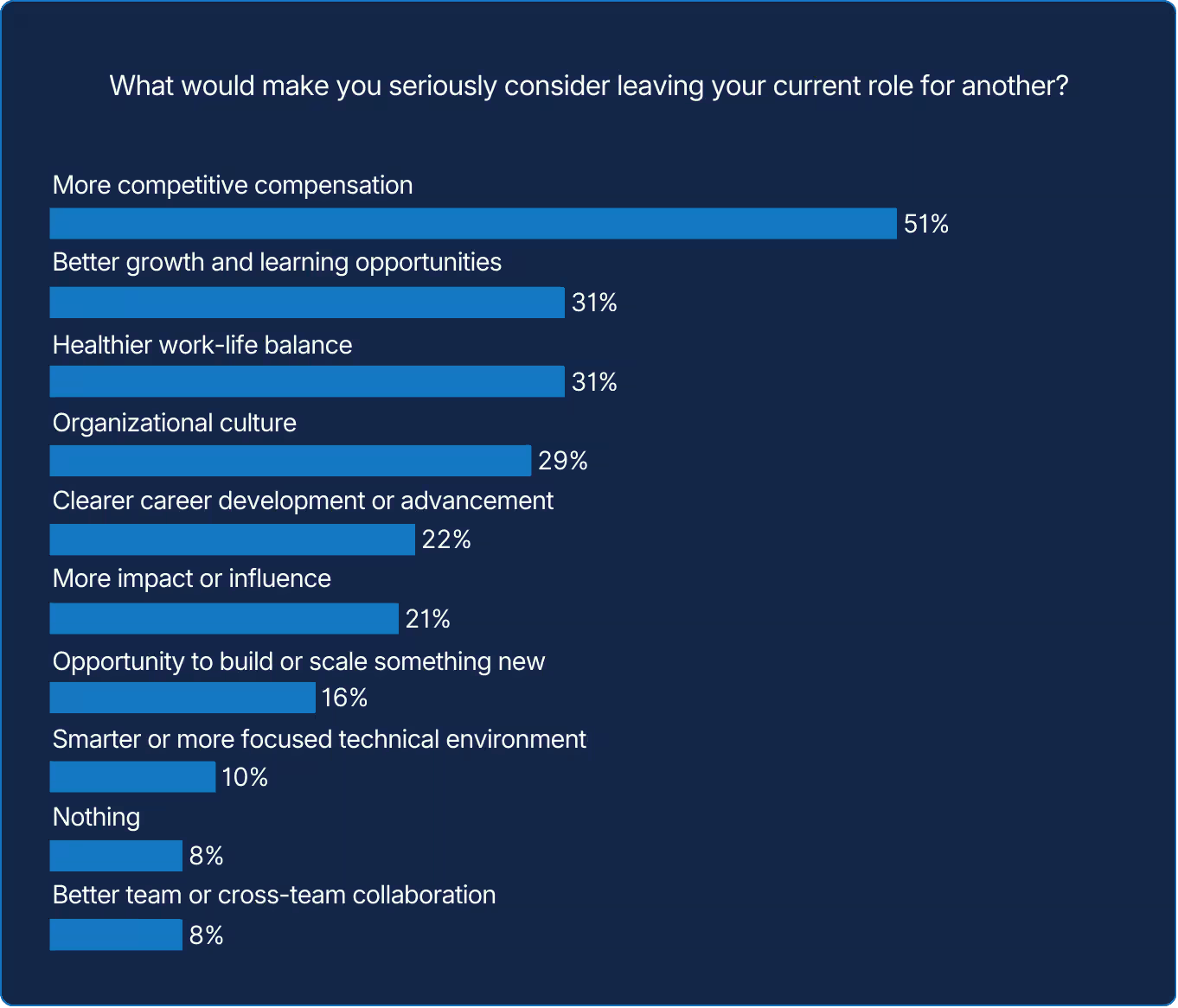

People stay where they can evolve. Reliability work demands endurance, and endurance requires renewal. Career development is not a perk; it is preventive maintenance for people. The next incident may not begin in code but in the quiet fatigue of talent left unstretched or unfulfilled.

Ambition rises with rank, and management are most motivated by roles promising stronger learning. When managers and directors stop stretching, opportunities beneath them shrink for everyone. Reliability depends on continual renewal: learning drives resilience more than any dashboard or metric.

Reliability doesn’t begin in code; it begins in capability.

Systems evolve only as fast as the people maintaining them, yet the data reveals a troubling paradox. SREs know learning is essential, but few have the time or permission to pursue it. Most squeeze in a few hours a month, often after hours, in the margins of production. Only six percent say they have dedicated, protected learning time. That means in most organizations, curiosity runs on borrowed energy.

Learning isn’t just a luxury anymore. It’s the fuel for resilience. The more complex and AI-infused our systems become, the more engineers must continuously adapt, reframe, and retool. Knowledge decay is now a reliability risk. Teams that fail to invest in learning are burning future uptime.

When asked what would make them leave, respondents didn’t just cite pay. Rather, they named growth, balance, and culture. That’s an important cultural insight, since those are reasons why employees would consider leaving. Maintaining systems is easier when engineers are regularly learning. Neglecting skill growth can leave teams exposed to challenges that become harder to solve over time.

Learning, then, is the infrastructure of growth. It’s how organizations future-proof both their people and their platforms. The next leap in reliability won’t come from another dashboard. It will come from the hours you defend for skill-building, exploration, and reflection.

Eight Years of the Reliability Arc

Eight years of The SRE Report remind me that reliability is a journey. And eight years of the journey remind me of the stories. Stories of incidents and recoveries. Of criticism and recognition. Of both answering and creating questions.

It’s because of these stories that The SRE Report has meant so much. Every year, I hear from people who use the data to guide a decision, start a discussion, or defend an idea. Sometimes they also challenge what we write. They disagree, question, push back, or insist we missed something important.

And that is exactly how it should be.

Reliability grows stronger when it is examined from every angle, not only when it is agreed upon. The report belongs to everyone who takes the time to share, to respond, and to debate in good faith. It reflects a community that continues to question itself, and in doing so, continues to improve.

For that, all of us who have poured our time and energy into this report thank you. You kept the work honest, relevant, and alive.

As this year’s report closes, the story does not. There will be new questions, patterns, voices, and debates. Reliability will keep moving, as it always has, carried by those who keep writing the next chapter.

SRE Report Passioneer

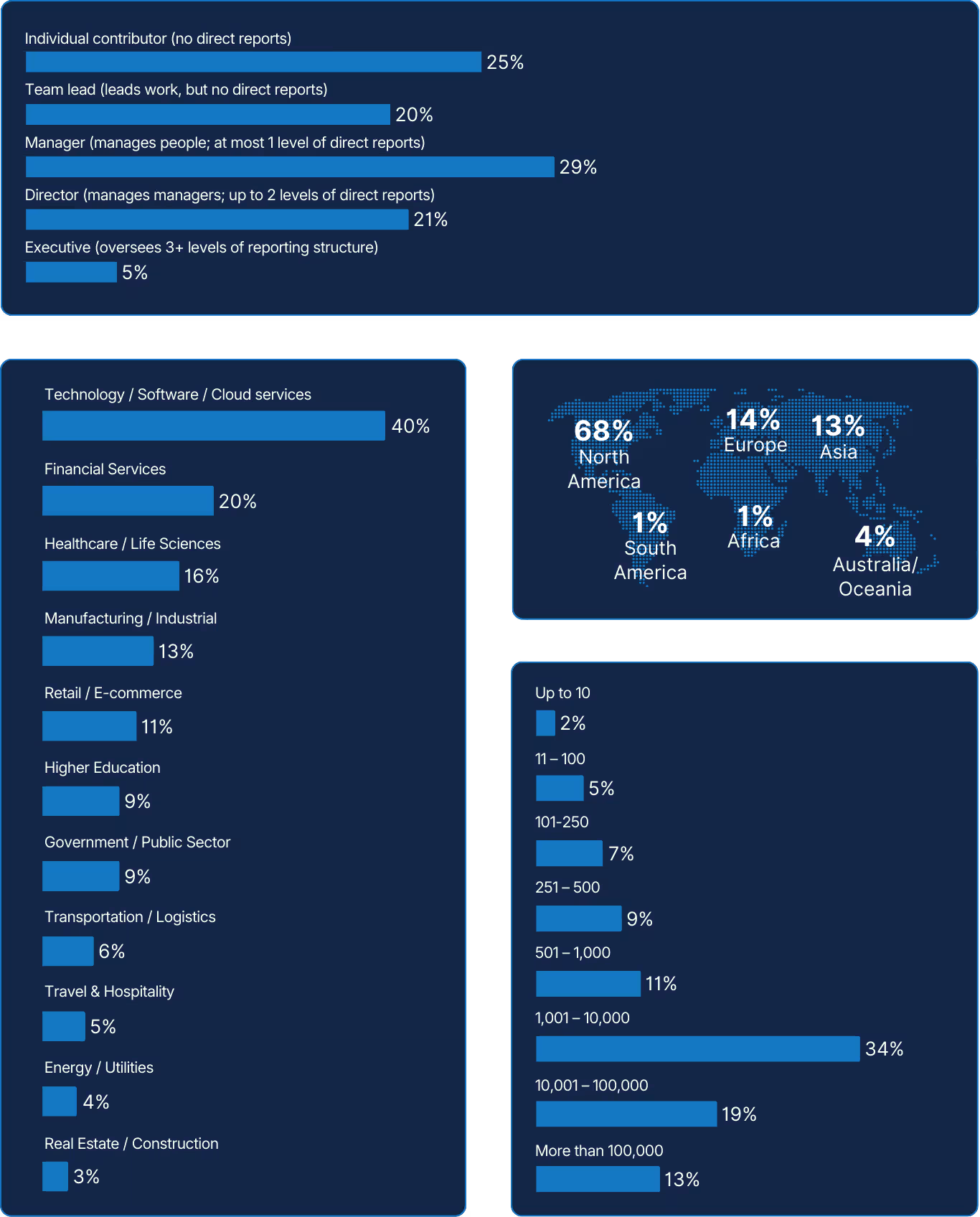

The SRE Survey, used to generate insights for this report, was open during July and August 2025. The survey received 418 responses from all across the world, and from all types of reliability roles and ranks.

Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) is a longstanding mechanism in place on the IP stack to allow the network help endpoints "foresee" congestion between them. The concept is straightforward… If a close-to-be-congested piece of network equipment, such as a middle router, could tell its destination, "Hey, I'm almost congested! Can you two guys slow down your data transmission? Otherwise, I’m worried I will start to lose packets...", then the two endpoints can react in time to avoid the packet loss, paying only the price of a minor slow down.

ECN bleaching occurs when a network device at any point between the source and the endpoint clears or “bleaches” the ECN flags. Since you must arrive at your content via a transit provider or peering, it’s important to know if bleaching is occurring and to remove any instances.

With Catchpoint’s Pietrasanta Traceroute, we can send probes with IP-ECN values different from zero to check hop by hop what the IP-ECN value of the probe was when it expired. We may be able to tell you, for instance, that a domain is capable of supporting ECN, but an ISP in between the client and server is bleaching the ECN signal.

ECN is an essential requirement for L4S since L4S uses an ECN mechanism to provide early warning of congestion at the bottleneck link by marking a Congestion Experienced (CE) codepoint in the IP header of packets. After receipt of the packets, the receiver echoes the congestion information to the sender via acknowledgement (ACK) packets of the transport protocol. The sender can use the congestion feedback provided by the ECN mechanism to reduce its sending rate and avoid delay at the detected bottleneck.

ECN and L4S need to be supported by the client and server but also by every device within the network path. It only takes one instance of bleaching to remove the benefit of ECN since if any network device between the source and endpoint clears the ECN bits, the sender and receiver won’t find out about the impending congestion. Our measurements examine how often ECN bleaching occurs and where in the network it happens.

ECN has been around for a while but with the increase in data and the requirement for high user experience particularly for streaming data, ECN is vital for L4S to succeed, and major investments are being made by large technology companies worldwide.

L4S aims at reducing packet loss - hence latency caused by retransmissions - and at providing as responsive a set of services as possible. In addition to that, we have seen significant momentum from major companies lately - which always helps to push a new protocol to be deployed.

If ECN bleaching is found, this means that any methodology built on top of ECN to detect congestion will not work.

Thus, you are not able to rely on the network to achieve what you want to achieve, i.e., avoid congestion before it occurs – since potential congestion is marked with Congestion Experienced (CE = 3) bit when detected, and bleaching would wipe out that information.

The causes behind ECN bleaching are multiple and hard to identify, from network equipment bugs to debatable traffic engineering choices and packet manipulations to human error.

For example, bleaching could occur from mistakes such as overwriting the whole ToS field when dealing with DSCP instead of changing only DSCP (remember that DSCP and ECN together compose the ToS field in the IP header).

Nowadays, network operators have a good number of tools to debug ECN bleaching from their end (such as those listed here) – including Catchpoint’s Pietrasanta Traceroute. The large-scale measurement campaign presented here is an example of a worldwide campaign to validate ECN readiness. Individual network operators can run similar measurement campaigns across networks that are important to them (for example, customer or peering networks).

The findings presented here are based on running tests using Catchpoint’s enhanced traceroute, Pietrasanta Traceroute, through the Catchpoint IPM portal to collect data from over 500 nodes located in more than 80 countries all over the world. By running traceroutes on Catchpoint’s global node network, we are able to determine which ISPs, countries and/or specific cities are having issues when passing ECN marked traffic. The results demonstrate the view of ECN bleaching globally from Catchpoint’s unique, partial perspective. To our knowledge, this is one of the first measurement campaigns of its kind.

Beyond the scope of this campaign, Pietrasanta Traceroute can also be used to determine if there is incipient congestion and/or any other kind of alteration and the level of support for more accurate ECN feedback, including if the destination transport layer (either TCP or QUIC) supports more accurate ECN feedback.